On "Transformation" and Government IT

11 Feb 2017“You may find yourself,

In a beautiful house,

With a beautiful wife.

You may ask yourself,

well, how did I get here?”

– David Byrne, Once In a Lifetime

I’ve spilled a lot of electrons over the last 5 years talking about IT failures in the BC government (ICM, BCeSIS, NRPP, CloudBC), and a recurring theme in the comments is “how did this happen?” and “are we special or does everybody do this?”

The answer is nothing more sophisticated than “big projects tend to fail”, usually because more people on an IT project just adds to organizational churn: more reporting, more planning, more reviewing of same, all undertaken by the most expensive managerial resources.

That being so, why do we keep approving and attempting big IT projects? BC isn’t unique in doing so, though we have our own organizational tale to tell.

“Transformation”

Both the social services Integrated Case Management (2009) and the Natural Resources Permitting Project (2013) projects were born out of “transformation” intiatives, attempts to restructure the business of a Ministry around new principles of authority and information flow.

Even for businesses as structured and regimented as a Department of Motor Vehicles, these projects can be risky. For a Ministry like Children & Families, where the stakes are children’s lives, and the evaluations of the facts of cases are necessarily subjective, the risk levels are even higher.

Nonetheless, in the mid 2000’s, the Province gave the Ministry of Management Services a new mission, to “champion the transformation of government service delivery to respond to the everyday needs of citizens, businesses and the public sector.” In particular, the IT folks in the Chief Information Officer’s department took this mission in hand. This may be a clue as to why IT projects became the central pivot for “transformation” initiatives.

Around the same time, the term “citizen centred service delivery” began to show up in Ministry Service Plans. Ministries were encouraged to pursue this new goal, with the assistance of Management Services (later renamed Citizens’ Services). This activity reached a climax in 2010, with the release of Citizens @ The Centre: B.C. Government 2.0 by then Deputy to the Premier Alan Seckel.

The “government 2.0” bit is a direct echo of hype from south of the border, where in 2009 meme-machine Tim O’Reilly kicked off a series of conferences and articles on “Government 2.0” as a counterpart to his “web 2.0” meme.

Enthusiasm for technology-driven “government as a platform” resulted in some positive side effects, such as the “open data” movement, and the creation of alternative in-sourced delivery organizations, like the UK Government Digital Service and the American 18F organization in the General Service Administration. In BC the technology mania also wafted over the top levels of civil service, resulting in the Citizens @ The Centre plan.

As a result, the IT inmates took over the asylum. Otherwise sane Ministries were directed to produce “Transformation and Technology Plans” to demonstrate their alignment with the goals of “Citizens @ the Centre”. Education, Transportation, Natural Resources and presumbly all the rest produced these plans during what turned out to be the final years of Premier Gordon Campbell’s rule.

The 2011 change in leadership from Gordon Campbell’s technocratic approach to the “politics über alles” style of Christie Clark has not substantially reduced the momentum of IT-driven transformation projects.

Part of this may be a matter of senior leadership personalities: the current Deputy to the Premier, Kim Henderson was leading Citizen’s Services when it produced Citizens @ The Centre; the former CIO Dave Nikolejsin, an architect of the catastrophic ICM project, remains involved in the ongoing NRPP transformation project, despite his new perch in the Ministry of Natural Gas Development.

Ballooning Budgets

The IT-led do-goodism of “transformation” explains to some extent how systems became the organizing principle for these disruptive projects, but it doesn’t fully explain their awesome size. Within my own professional memory, only 15 years ago, $10M was an surprisingly large IT opportunity in BC. Now I can name half a dozen projects that have exceeded $100M.

The social services Integrated Case Management project provides an interesting study in how a budget can blow up.

“Integrated Case Management” as a desirable concept was suggested by the 1996 Gove Report, (yes, 1996) leading to an “Integrated Case Management Policy” in 1998, and by 1999 a Ministry working group examining “off-the-shelf” (COTS) technology solutions. The COTS review did not turn up a suitable solution, and the Ministry buried itself in a long “requirements gathering” process, culminating in a working prototype by 2002. In 2003, an RFP was issued to expand the prototype into a pilot for a few hundred users.

The 2003 contract to build out the pilot was awarded to GDS & Associates Systems in the amount of $142,800. No, I didn’t drop any zeroes. Six years before a $180,000,000 ICM contract was awarded to Deloitte, the Ministry thought a working pilot could be developed for 1/1000 of the cost.

What happened after that is a bit of a mystery. Presumably the pilot process failed in some way (would love to know! leave a comment! send an email!) because in 2007 the government was back with a Request to procure a “commercial off-the-shelf” integrated case management solution.

This was the big kahuna. Instead of piloting a small solution and incrementally rolling out, the government already had plans to roll the solution out to over 5000 government workers and potentially 12000 contractors. And the process was going to be incredibly easy:

- Phase 1: Procure Software

- Phase 2: Planning and Systems Integration

- Phase 3: Blueprint and Configure

- Phase 4: Implementation

- Phase 5: Future Implementation

Here’s where things get confusing. Despite using “off-the-shelf” software to avoid software development risks, and having a simple plan to just “configure” the software and roll it out, the new project was tied to a capital plan for $180M dollars, 1000 times the budget of the custom pilot software from a few years earlier.

Why?

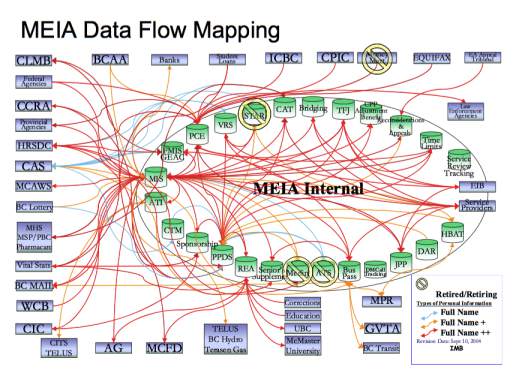

Whereas the original pilot aimed to provide a new case management solution, full stop, the new project seems to have been designed to “boil the ocean”, touching and replacing hundreds of systems throughout the Ministry.

At this point the psychology of capital financing and government approvals starts to come into play. Capital financing can be hard to get. Large plans must be written and costed, and business cases built to show “return on investment” to Treasury Board.

One way to gain easy “return” is to take all the legacy systems in the organization, fluff up their annual operating costs as much as possible, bundle them together and say “we’re going to replace all this, for an annual savings of $X, which in conjunction with efficiencies $Y from our new technology and centralized maintenance gives us a positive ROI!”

I’m pretty sure this psychology applies, since almost exactly the same arguments backstop the “business case” for the ongoing Natural Resource Permitting Project.

A natural effect of bundling multiple system integrations is to blow up the budget size. This is actually a Good Thing (tm) from the point of view of technology managers, since it provides some excellent resumé points: “procured and managed 9-digit public IT project.”

A manager who successfully delivers a superb $4M IT project gets a celebratory dinner at the pub; a manager who brings even a terrible $140M IT project to “completion” can write her ticket in IT consulting.

The only downside of huge IT projects is that they fail to provide value to end-users a majority of the time, and of course they soak the taxpayers (or shareholders in the case of private sector IT failures, which happen all the time) for far more money than they should.

Can We Stop? Should We?

We really should stop. The source of the problems are pretty clear: overly large projects, and heavily outsourced IT.

Even the folks at the very top can see the problem and describe it, if they have the guts.

David Freud, former Conservative minister at the UK Department for Work and Pensions, was in charge of “Universal Credit” a large social services transformation project, which included a large poorly-built IT component – a project similar in scope to our ICM. He had this to say in a debrief about what he learned in the process:

The implementation was harder than I had expected. Maybe that was my own naivety. What I didn’t know, and I don’t think anyone knew, was how bad a mistake it had been for all of government to have sent out their IT.

It happened in the 1990s and early 2000s. You went to these big firms to build your IT. I think that was a most fundamental mistake, right across government and probably across government in the western world…

We talk about IT as something separate but it isn’t. It is part of your operating system. It’s a tool within a much better system. If you get rid of it, and lose control of it, you don’t know how to build these systems.

So we had an IT department but it was actually an IT commissioning department. It didn’t know how to do the IT.

What we actually discovered through the (UC) process was that you had to bring the IT back on board. The department has been rebuilding itself in order to do that. That is a massive job.

The solution will be difficult, because it will involve re-building internal IT skills in the public service, a work environment that is drastically less flexible and rewarding than the one on offer from the private sector. However, what the public service has going for it is a mission. Public service is about, well, “public service”. And IT workers are the same as anyone else in wanting their work to have value, to help people, and to do good.

The best minds of my generation are thinking about how to make people click ads.

– Jeffrey Hammerbacher

When the Obamacare healthcare.gov site, built by Canadian enterprise IT consultant CGI, cratered shortly after launch, it was customer-focused IT experts from Silicon Valley and elsewhere who sprang into action to rescue it. And when they were done, many of them stayed on, founding the US Digital Service to bring modern technology practices into the government. They’re paid less, and their offices aren’t as swank, but they have a mission, beyond driving profit to shareholders, and that’s a motivating thing.

Government can build up a new IT workforce, and start building smaller projects, faster, and stop boiling the ocean, but they have to want to do it first. That’ll take some leadership, at the political level as well as in the civil service. IT revitalization is not a partisan thing, but neither is it an easy thing, or a sexy thing, so it’ll take a politician with some guts to make it a priority.