Data Science is Getting Ducky

19 Dec 2023For a long time, a big constituency of users of PostGIS has been people with large data analytics problems that crush their desktop GIS systems. Or people who similarly find that their geospatial problems are too large to run in R. Or Python.

These are data scientists or adjacent people. And when they ran into those problems, the first course of action would be to move the data and parts of the workload to a “real database server”.

This all made sense to me.

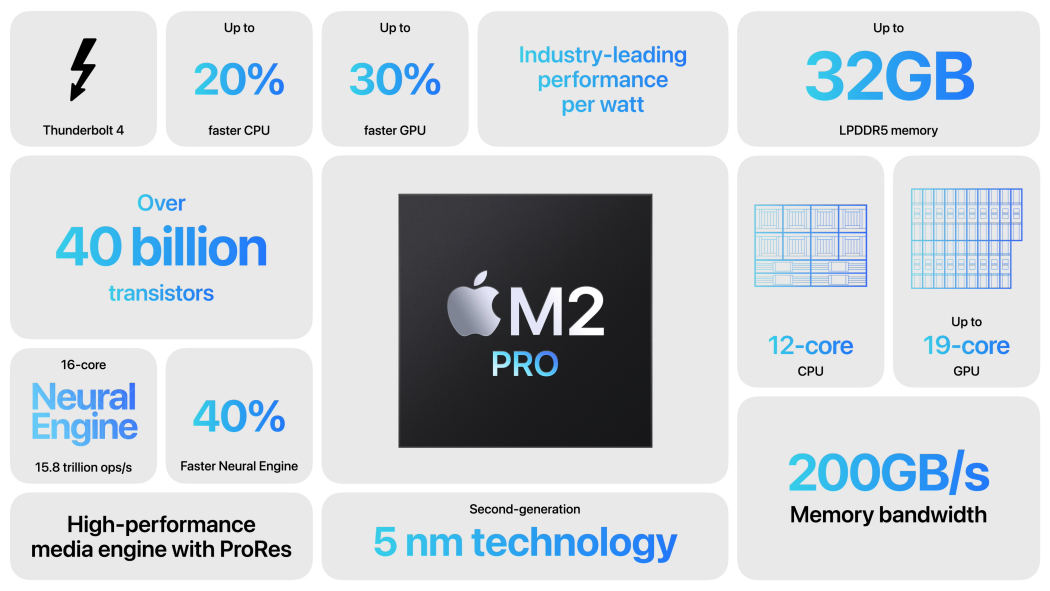

But recently, something transformative happened – Crunchy Data upgraded my work laptop to a MacBook Pro.

Suddenly a GEOS compile that previously took 20 minutes, took 45 seconds.

I now have processing power on my local laptop that previously was only available on a server. The MacBook Pro may be a leading indicator of this amount of power, but the trend is clear.

What does that mean for default architectures and tooling?

Well, for data science, it means that a program like DuckDB goes from being a bit of a curiosity, to being the default tool for handling large data processing workloads.

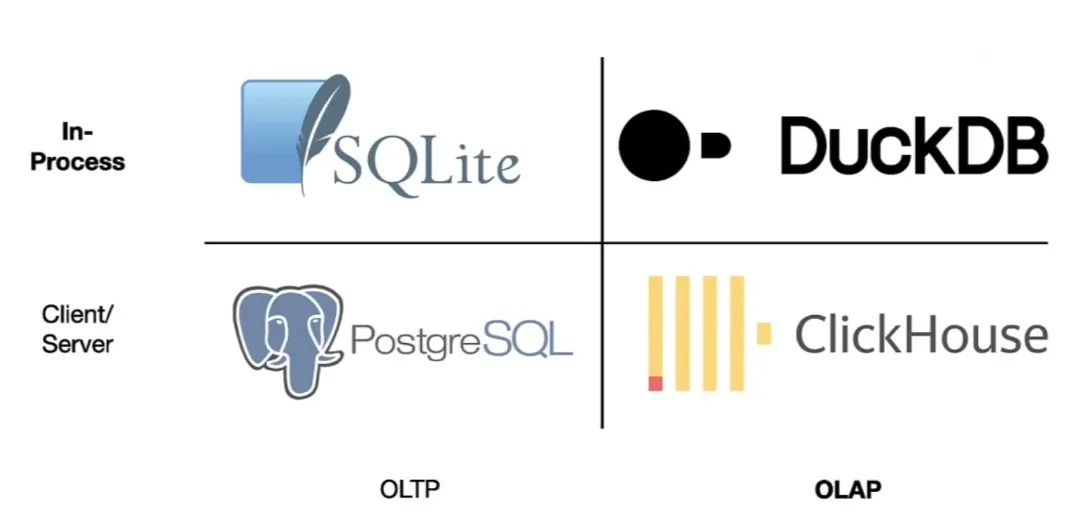

What is DuckDB? According to the web site, it is “an in-process SQL OLAP database management system”. That doesn’t sound like a revolution in data science (it sounds really confusing).

But consider what DuckDB rolls together:

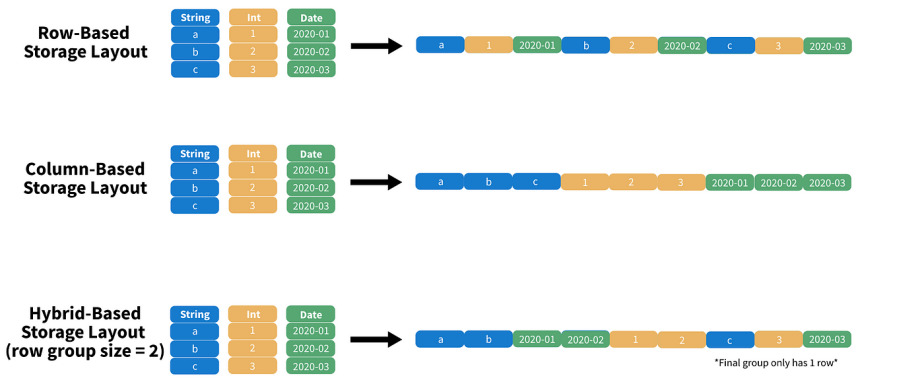

- A column-oriented processing engine that makes the most efficient possible use of the processors in modern computers. Parallelism to ensure all CPUs are made use of, and low-level optimizations to ensure each tick of those processors pushes as much data through the pipe as possible.

- Wide ranging support for different data formats, so that integration can take place on-the-fly without requiring translation or sometimes even data download steps.

Having those things together makes it a data science power tool, and removes a lot of the prior incentive that data scientists had to move their data into “real” databases.

When they run into the limits of in-memory analysis in R or Python, they will instead serialize their data to local disk and use DuckDB to slam through the joins and filters that were blowing out their RAM before.

They will also take advantage of DuckDB’s ability to stream remote data from data lake object stores.

What, stream multi-gigabyte JSON files? Well, yes that’s possible, but it’s not where the action is.

The CPU is not the only laptop component that has been getting ridiculously powerful over the past few years. The network pipe that connects that laptop to the internet has also been getting both wider and lower latency with every passing year.

As the propect of streaming data for analysis has come into view, the formats for remote data have also evolved. Instead of JSON, which is relatively fluffy, and hard to efficiently filter, the Parquet format is becoming a new standard for data lakes.

Parquet is a binary format, that organizes the data into blocks for efficient subsetting and processing. A DuckDB query to a properly organized Parquet time series file might easily pull only records for 2 of 20 columns, and 1 day of 365, reducing a multi-gigabyte download to a handful of megabytes.

The huge rise in available local computation, and network connectivity is going to spawn some new standard architectures.

Imagine a “two tier” architecture where tier one is an HTTP object store and tier two is a Javascript single page app? The COG Explorer has already been around for a few years, and it’s just such a two tier application.

(For fun, recognize that an architecture where the data are stored in an access-optimized format, and access is via primitive file-system requests, while all the smarts are in the client-side visualization software is… the old workstation GIS model. Everything old is new again.)

The technology is fresh, but the trendline is pretty clear. See Kyle Barrron’s talk about GeoParquet and DeckGL for a taste of where we are going.

Meanwhile, I expect that a lot of the growth in PostGIS / PostgreSQL we have seen in the data science field will level out for a while, as the convenience of DuckDB takes over a lot of workloads.

The limitations of Parquet (efficient remote access limited to a handful of filter variables being the primary one, as will cojoint spatial/non-spatial filter and joins) will still leave use cases that require a “real” database, but a lot of people who used to reach for PostGIS will be reaching for Duck, and that is going to change a lot of architectures, some for the better, and some for the worse.