31 May 2021

Twenty years ago today, the first email on the postgis users mailing list (at that time hosted on yahoogroups.com) was sent, announcing the first numbered release of PostGIS.

The early history of PostGIS was tightly bound to a consulting company I had started a few years prior, Refractions Research. My first contracts ended up being with British Columbia (BC) provincial government managers who, for their own idiosyncratic reasons, did not want to work with ESRI software, and as a result our company accrued skills and experience beyond what most “GIS companies” in the business had.

We got good at databases, and the FME. We got good at Perl, and eventually Java. We were the local experts in a locally developed (and now defunct) data analysis tool called Facet, which was the meat of our business for the first four years or so.

That Facet tool was a key part of a “watershed analysis atlas” the BC government commissioned from Facet in the late 1990’s. We worked as sub-contractors, building the analytical routines that would suck in dozens of environmental layers, chop them up by watershed, and spit out neat tables and maps, one for each watershed. Given the computational power of the era, we had to use multiple Sun workstations to run the final analysis province-wide, and to manage the job queue, and keep track of intermediate results, we placed them all into tables in PostgreSQL.

Putting the chopped up pieces of spatial data as blobs into PostgreSQL was what inspired PostGIS. It seemed really obvious that we had the makings of an interactive real-time analysis engine, with all this processed data in the database, if we could just do more with the blobs than only stuff them in and pull them out.

Maybe We Should do Spatial Databases?

Reading about spatial databases circa 2000 you would find that:

This led to two initiatives on our part, one of which succeeded and the other of which did not.

First, I started exploring whether there was an opportunity in the BC government for a consulting company that had skill with Oracle’s spatial features. BC was actually standardized on Oracle as the official database for all things governmental. But despite working with the local sales rep and looking for places where spatial might be of interest, we came up dry.

The existing big Oracle ministries (Finance, Justice) didn’t do spatial, and the heavily spatial natural resource ministries (Forests, Environment) were still deeply embedded in a “GIS is special” head space, and didn’t see any use for a “spatial database”. This was all probably a good thing, as it turned out.

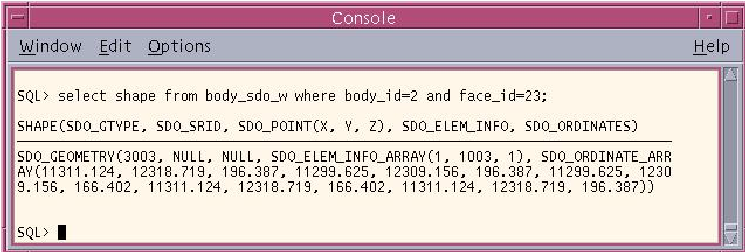

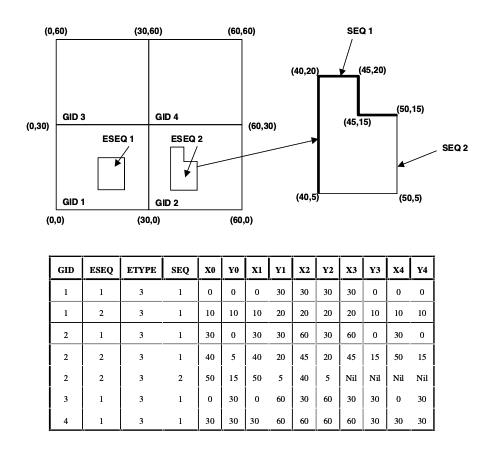

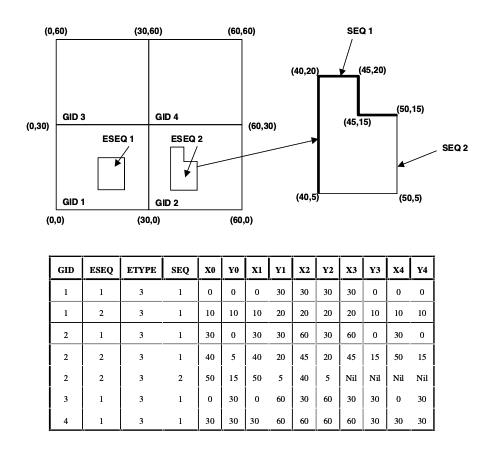

Our second spatial database initiative was to explore whether any of the spatial models described in the OpenGIS Simple Features for SQL specification were actually practical. In addition to describing the spatial types and functions, the specification described three ways to store the spatial part of a table.

- In a set of side tables (scheme 1a), where each feature was broken down into x’s and y’s stored in rows and columns in a table of numbers.

- In a “binary large object” (BLOB) (scheme 1b).

- In a “geometry type” (scheme 2).

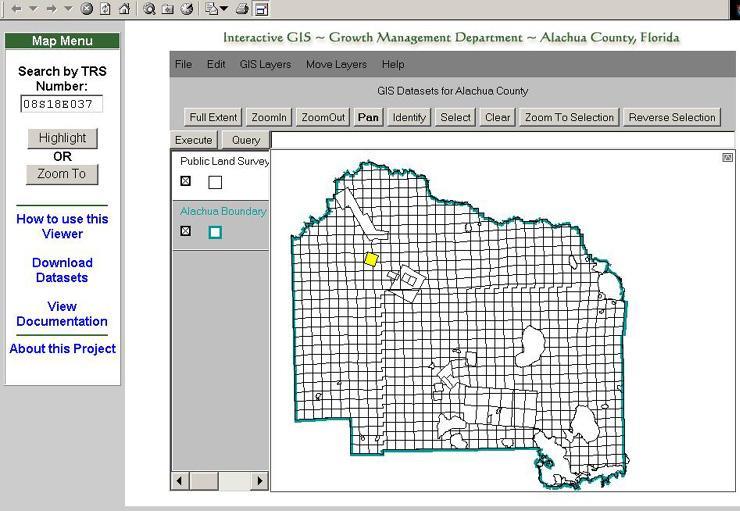

Since the watershed work had given us experience with PostgreSQL, we carried out the testing with that database, examining: could we store spatial data in the database and pull it out efficiently enough to make a database-backed spatial viewer.

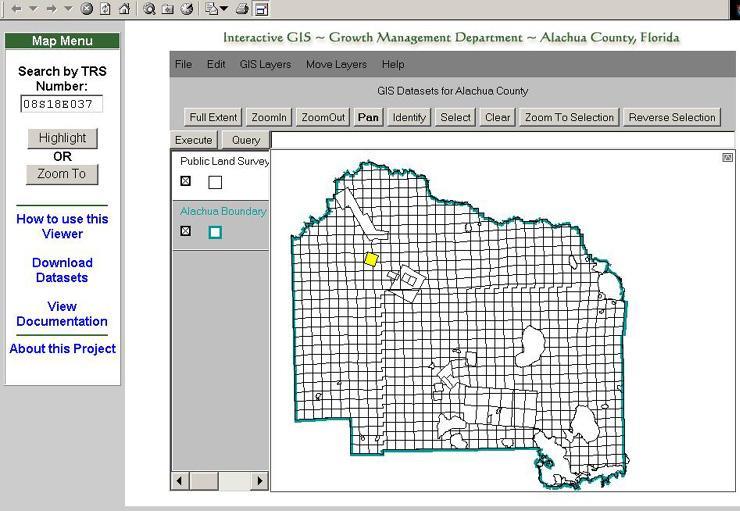

For the viewer part of the equation, we ran all the experiments using a Java applet called JShape. I was quite fond of JShape and had built a few little map viewer web pages for clients using it, so hooking it up to a dynamic data source rather than files was a rather exciting prospect.

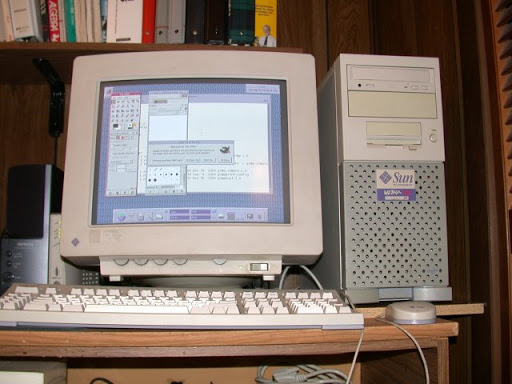

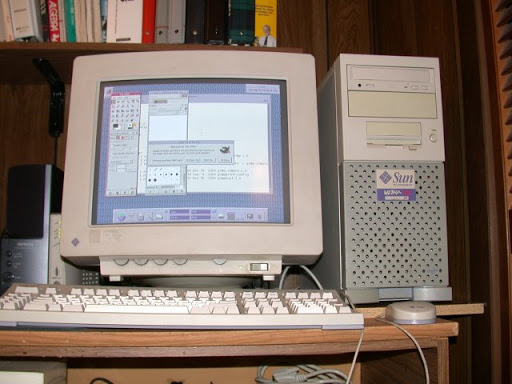

All the development was done on the trusty Sun Ultra 10 I had taken out a $10,000 loan to purchase when starting up the company. (At the time, we were still making a big chunk of our revenue from programming against the Facet software, which only ran on Sun hardware.)

- The first experiment, shredding the data into side tables, and then re-constituting it for display was very disappointing. It was just too slow to be usable.

- The second experiment, using the PostgreSQL BLOB interface to store the objects, was much faster, but still a little disappointing. And there was no obvious way to add an index to the data.

Breakthrough

At this point we almost stopped: we’d tried all the stuff explained in the user-level documentation for PostgreSQL. But our most sophisticated developer, Dave Blasby, who had actually studied computer science (most of us had mathematics and physics degrees), and was unafraid of low-level languages, looked through the PostgreSQL code and contrib section and said he could probably do a custom type, given some time.

So he took several days and gave it a try. He succeeded!

When Dave had a working prototype, we hooked it up to our little applet and the thing sang. It was wonderfully quick, even when we loaded up quite large tables, zooming around the spatial data and drawing our maps. This is something we’d only seen on fancy XWindows displays on UNIX workstations and now were were doing it in an applet on ordinary PC. It was quite amazing.

We had gotten a lot of very good use out of the PostgreSQL database, but there was no commercial ecosystem for PostgreSQL extensions, so it seemed like the best business use of PostGIS was to put it “out there” as open source and see if it generated some in-bound customer traffic.

At the time, Refractions had perhaps 6 staff (it’s hard to remember precisely) and many of them contributed, both to the initial release and over time.

- Dave Blasby continued polishing the code, adding some extra functions that seemed to make sense.

- Jeff Lounsbury, the only other staffer who could write C, took up the task of a utility to convert Shape files into SQL, to make loading spatial data easier.

- I took on the work of setting up a Makefile for the code, moving it into a CVS repository, writing the documentation, and getting things ready for open sourcing.

- Graeme Leeming and Phil Kayal, my business partners, put up with this apparently non-commercial distraction. Chris Hodgson, an extremely clever developer, must have been busy elsewhere or perhaps had not joined us just yet, but he shows up in later commit logs.

Release

Finally, on May 31, Dave sent out the initial release announcement. It was PostGIS 0.1, and you can still download it, if you like. This first release had a “geometry” type, a spatial index using the PostgreSQL GIST API, and these functions:

- npoints(GEOMETRY)

- nrings(GEOMETRY)

- mem_size(GEOMETRY)

- numb_sub_objs(GEOMETRY)

- summary(GEOMETRY)

- length3d(GEOMETRY)

- length2d(GEOMETRY)

- area2d(GEOMETRY)

- perimeter3d(GEOMETRY)

- perimeter2d(GEOMETRY)

- truly_inside(GEOMETRY, GEOMETRY)

The only analytical function, “truly_inside()” just tested if a point was inside a polygon. (For a history of how PostGIS got many of the other analytical functions it now has, see History of JTS and GEOS on Martin Davis’ blog.)

Reading through those early mailing list posts from 2001, it’s amazing how fast PostGIS integrated into the wider open source geospatial ecosystem. There are posts from Frank Warmerdam of GDAL and Daniel Morissette of MapServer within the first month of release. Developers from the Java GeoTools/GeoServer ecosystem show up early on as well.

There was a huge demand for an open source spatial database, and we just happened to show up at the right time.

Where are they Now?

- Graeme, Phil, Jeff and Chris are still doing geospatial consulting at Refractions Research.

- Dave maintained and improved PostGIS for the first couple years. He left Refractions for other work, but still works in open source geospatial from time to time, mostly in the world of GeoServer and other Java projects.

- I found participating in the growth of PostGIS very exciting, and much of my consulting work… less exciting. In 2008, I left Refractions and learned enough C to join the PostGIS development community as a contributor, which I’ve been doing ever since, currently as a Executive Geospatial Engineer at Crunchy Data.

06 May 2021

Yesterday I talked about all-things-GDAL (or at least all the things that fit in 30 minutes) with MapScaping Podcast’s Daniel O’Donohue.

In the same way that Linux is the under-appreciated substrate of modern computing, GDAL is the under-appreciated substrate of modern geospatial data management. If the compute is running in the cloud, it’s probably running on Linux; if the geospatial data are flowing through the cloud, they’re probably flowing through GDAL.

At the same time as it has risen to being the number one spatial data processing tool in the world (by volume anyways), GDAL has maintained an economic support model from the last century. One maintainer (currently Even Rouault), earning a living with new feature development, and doing all the work of code quality, integration, testing, documentation, and promotion as a loss leader. This model burns out maintainers, and it doesn’t ask the organizations that gain the most value from GDAL (the ones pushing terrabytes of pixels through the cloud) to contribute commensurate with the value they receive.

With the new GDAL sponsor model, the organizations who receive the most value are stepping up to do their share. If your organization uses GDAL, and especially if it uses it in volume, consider joining the other sponsors in making sure GDAL remains high quality and cutting edge by sponsoring.

Thanks Daniel, for having me on!

04 May 2021

So, this happened:

Basically a GeoDjango user posted some workarounds to some poor performance in spatial queries, and the original query was truly awful and the workaround not a lot better, so I snarked, and the GeoDjango maintainer reacted in kind.

Sometimes a guy just wants to be a prick on the internet, you know? But still, I did raise the red flag of snarkiness, so it it seems right and proper to pay the fine.

I come to this not knowing entirely the contract GeoDjango has with its users in terms of “hiding the scary stuff”, but I will assume for these purposes that:

- Data can be in any coordinate system.

- Data can use geometry or geography column types.

- The system has freedom to create indexes as necessary.

So the system has to cover up a lot of variability in inputs to hide the scary stuff.

We’ll assume a table name of the_table a geometry column name of geom and a geography column name of geog.

Searching Geography

This is the easiest, since geography queries conform to the kind of patterns new users expect: the coordinates are in lon/lat but the distances are provided/returned in metres.

Hopefully the column has been spatially indexed? You can check in the system tables.

SELECT *

FROM pg_indexes

WHERE tablename = 'the_table';

Yes, there are more exact ways to query the system tables for this information, I give the simple example for space reasons.

If it has not been indexed, you can make a geography index like this:

CREATE INDEX the_table_geog_x

ON the_table

USING GIST (geog);

And then a “buffered” query, that finds all objects within a radius of an input geometry (any geometry, though only a point is shown here) looks like this.

SELECT *

FROM the_table

WHERE ST_DWithin(

the_table.geog,

ST_SetSRID(ST_MakePoint(%lon, %lat), 4326),

%radius

);

Note that there is no “buffering” going on here! A radius search is logically equivalent and does not pay the cost of building up buffers, which is an expensive operation.

Also note that, logically, ST_DWithin(A, B, R) is the same as ST_Distance(A, B) < R, but in execution the former can leverage a spatial index (if there is one) while the latter cannot.

Indexable Functions

Since I mention that ST_DWithin() is indexable, I should list all the functions that can make use of a spatial index:

And for a bonus there are also a few operators that access spatial indexes.

- geom_a && geom_b returns true if the bounding box of geom_a intersects the bounding box of geom_b in 2D space.

- geom_a &&& geom_b returns true if the bounding box of geom_a intersects the bounding box of geom_b in ND space (an ND index is required for this to be index assisted),

Searching Planar Geometry

If the data are planar, then spatial searching should be relatively easy, even if the input geometry is not in the same coordinate system.

First, is your data planar? Here’s a quick-and-dirty query that returns true for geographic data and false for planar.

SELECT srs.srtext ~ '^GEOGCS'

FROM spatial_ref_sys srs

JOIN geometry_columns gc

ON srs.srid = gc.srid

WHERE gc.f_table_name = 'the_table'

Again, do you have a spatial index on your geometry column? Check!

CREATE INDEX the_table_geom_x

ON the_table

USING GIST (geom);

Now, assuming query coordinates in the same planar projection as the data, a fast query will look like this:

SELECT *

FROM the_table

WHERE ST_DWithin(

geom,

ST_SetSRID(ST_MakePoint(%x, %y), %srid)

%radius

);

But what if users are feeding in queries in geographic coordinates? No problem, just convert them to planar before querying:

SELECT *

FROM the_table

WHERE ST_DWithin(

geom,

ST_Transform(

ST_SetSRID(ST_MakePoint(%lon, %lat), 4326),

%srid)

%radius

);

Note that here we are transforming the geography query to planar, not transforming the planar column to geographic!

Why? There’s only one query object, and there’s potentially 1000s of rows of table data. And also, the spatial index has been built on the planar data: it cannot assist the query unless the query is in the same projection.

Searching Lon/Lat Geometry

This is the hard one. It is quite common for users to load geographic data into the “geometry” column type. So the database understands them as planar (that’s what the geometry column type is for!) while their units (longitude and latitude) are in fact angular.

There are benefits to staying in the geometry column type:

- There are far more functions native to geometry, so you can avoid a lot of casting.

- If you are mostly working with planar queries you can get better performance from 2D functions.

However, there’s a huge downside: questions that expect metric answers or metric parameters can’t be answered. ST_Distance() between two geometry objects with lon/lat coordinates will return an answer in… “degrees”? Not really an answer that makes any sense, as cartesian math on anglar coordinates returns garbage.

So, how to get around this conundrum? First, the system has to recognize the conundrum!

- Is the column type “geometry”?

- Is the SRID a long/lat coordinate system? (See test query above.)

Both yes? Ok, this is what we do.

First, create a functional index on the geography version of the geometry data. (Since you’re here, make a standard geometry index too, for other purposes.)

CREATE INDEX the_table_geom_geog_x

ON the_table

USING GIST (geography(geom));

CREATE INDEX the_table_geom

ON the_table

USING GIST (geom);

Now we have an index that understands geographic coordinates!

All we need now is a way to query the table that uses that index efficiently. The key with functional indexes is to ensure the function you used in the index shows up in your query.

SELECT *

FROM the_table

WHERE ST_DWithin(

geography(geom),

geography(ST_SetSRID(ST_MakePoint(%lon, %lat), 4326))

%radius

);

What’s going on here? By using the “geography” version of ST_DWithin() (where both spatial arguments are of type “geography”) I get a search in geography space, and because I have created a functional index on the geography version of the “geom” column, I get it fully indexed.

Random Notes

- The user blog post asserts incorrectly that their best performing query is much faster because it is “using the spatial index”.

SELECT

"core_searchcriteria"."id",

"core_searchcriteria"."geo_location"::bytea,

"core_searchcriteria"."distance",

ST_DistanceSphere(

"core_searchcriteria"."geo_location",

ST_GeomFromEWKB('\001\001\000\000 \346\020\000\000\000\000\000\000\000@U@\000\000\000\000\000\000@@'::bytea)) AS "ds"

FROM "core_searchcriteria"

WHERE ST_DistanceSphere(

"core_searchcriteria"."geo_location",

ST_GeomFromEWKB('\001\001\000\000 \346\020\000\000\000\000\000\000\000@U@\000\000\000\000\000\000@@'::bytea)

) <= "core_searchcriteria"."distance";

-

However, the WHERE clause is just not using any of the spatially indexable functions. Any observed speed-up is just because it’s less brutally ineffecient than the other queries.

-

Why was the original brutally inefficient?

SELECT

"core_searchcriteria"."id",

"core_searchcriteria"."geo_location"::bytea,

"core_searchcriteria"."distance",

ST_Buffer(

CAST("core_searchcriteria"."geo_location" AS geography(POINT,4326)), "core_searchcriteria"."distance"

)::bytea AS "buff" FROM "core_searchcriteria"

WHERE ST_Intersects(

ST_Buffer(

CAST("core_searchcriteria"."geo_location" AS geography(POINT,4326)), "core_searchcriteria"."distance"),

ST_GeomFromEWKB('\001\001\000\000 \346\020\000\000\000\000\000\000\000@U@\000\000\000\000\000\000@@'::bytea)

)

- The WHERE clause converts the entire contents of the data column to geography and then buffers every single object in the system.

- It then compares all those buffered objects to the query object (what, no index? no).

- Since the column objects have all been buffered… any spatial index that might have been built on the objects is unusable. The index is on the originals, not on the buffered objects.

01 Apr 2021

Sometimes you just have to work with binary in your PostgreSQL database, and when you do the bytea type is what you’ll be using. There’s all kinds of reason to work with bytea:

- You’re literally storing binary things in columns, like image thumbnails.

- You’re creating a binary output, like an image, a song, a protobuf, or a LIDAR file.

- You’re using a binary transit format between two types, so they can interoperate without having to link to each others internal format functions. (This is my favourite trick for creating a library with optional PostGIS integration, like ogr_fdw.)

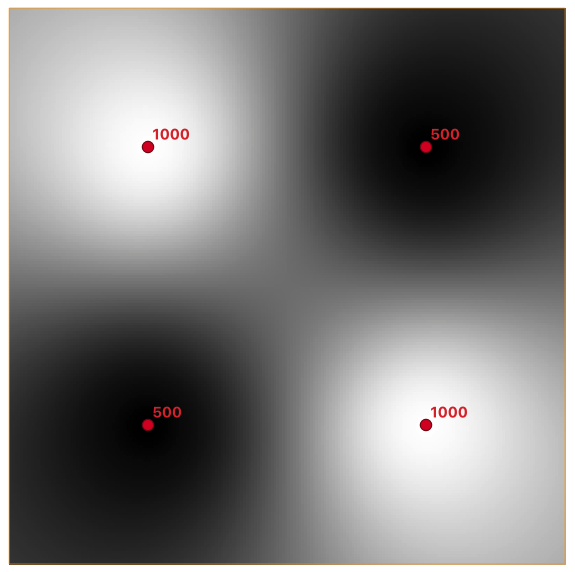

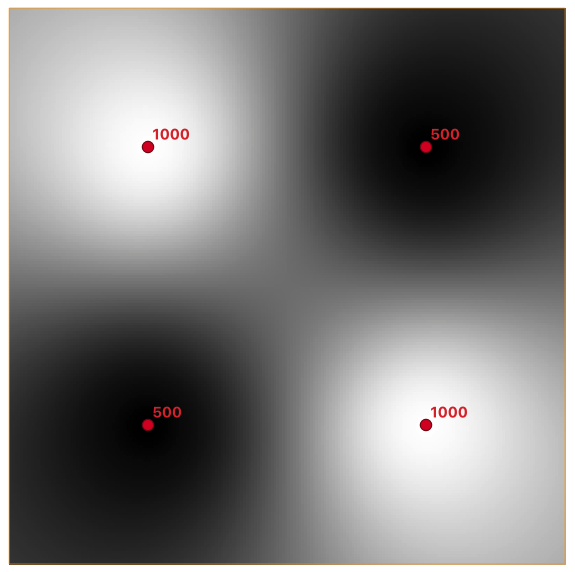

Today I was doing some debugging on the PostGIS raster code, testing out a new function for interpolating a grid surface from a non-uniform set of points, and I needed to be able to easily see what the raster looked like.

There’s a function to turn a PostGIS raster into a GDAL image format, so I could create image data right in the database, but in order to actually see the image, I needed to save it out as a file. How to do that without writing a custom program? Easy! (haha)

Basic steps:

- Pipe the query of interest into the database

- Access the image/music/whatever as a

bytea

- Convert that bytea to a hex string using

encode()

- Ensure psql is not wrapping the return in any extra cruft

- Pipe the hex return value into

xxd

- Redirect into final output file

Here’s what it would look like if I was storing PNG thumbnails in my database and wanted to see one:

echo "SELECT encode(thumbnail, 'hex') FROM persons WHERE id = 12345" \

| psql --quiet --tuples-only -d dbname \

| xxd -r -p \

> thumbnail.png

Any bytea output can be pushed through this chain, here’s what I was using to debug my ST_GDALGrid() function.

echo "SELECT encode(ST_AsGDALRaster(ST_GDALGrid('MULTIPOINT(10.5 9.5 1000, 11.5 8.5 1000, 10.5 8.5 500, 11.5 9.5 500)'::geometry, ST_AddBand(ST_MakeEmptyRaster(200, 400, 10, 10, 0.01, -0.005, 0, 0), '16BSI'), 'invdist' ), 'GTiff'), 'hex')" \

| psql --quiet --tuples-only grid \

| xxd -r -p \

> testgrid.tif

16 Dec 2020

This post originally appeared on the Crunchy Data blog.

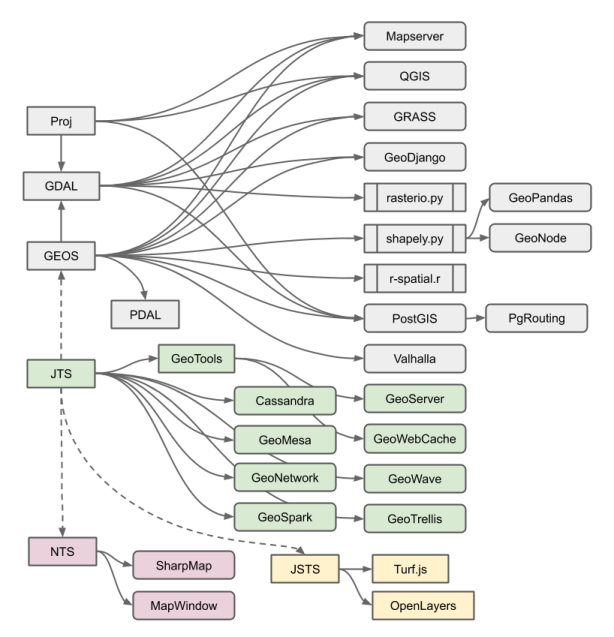

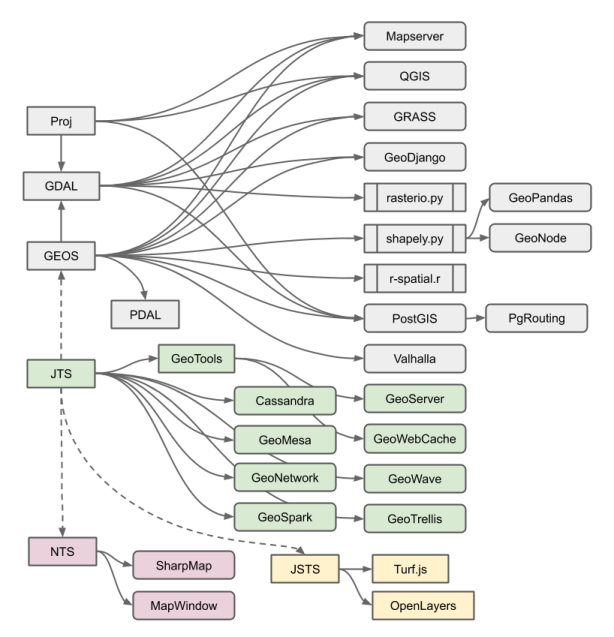

While we talk about “PostGIS” like it’s one thing, it’s actually the collection of a number of specialized geospatial libraries, along with a bunch of code of its own.

- PostGIS provides core functionality

- bindings to PostgreSQL, the types and indexes,

- format reading and writing

- basic algorithms like distance and area

- performance tricks like caching

- simple geometry manipulations (add a point, dump rings, etc)

- algorithms that don’t exist in the other libraries

- Proj provides coordinate system transformations

- GDAL provides raster algorithms and format supports

- GEOS provides computational geometry algorithms

- geometry relationships, like “intersects”, “touches” and “relate”

- geometry operations, like “intersection”, “union”

- basic algorithms, like “triangulate”

The algorithms in GEOS are actually a port to C++ of algoriths in the JTS Java library. The ecosystem of projects that depend on GEOS or JTS or one of the other language ports of GEOS is very large.

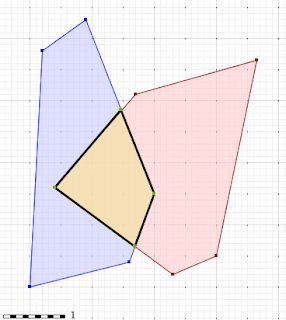

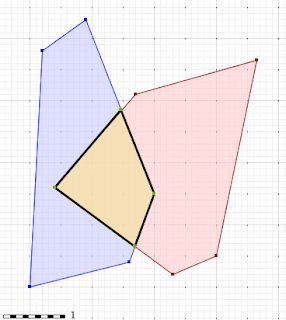

Overlay NG

Over the past 12 months, the geospatial team at Crunchy Data has invested heavily in JTS/GEOS development, overhauling the overlay engine that backs the Intersection, Union, Difference and SymDifference functions in all the projects that depend on the library.

The new overlay engine, “Overlay NG”, promises to be more reliable, and hopefully also faster for most common cases.

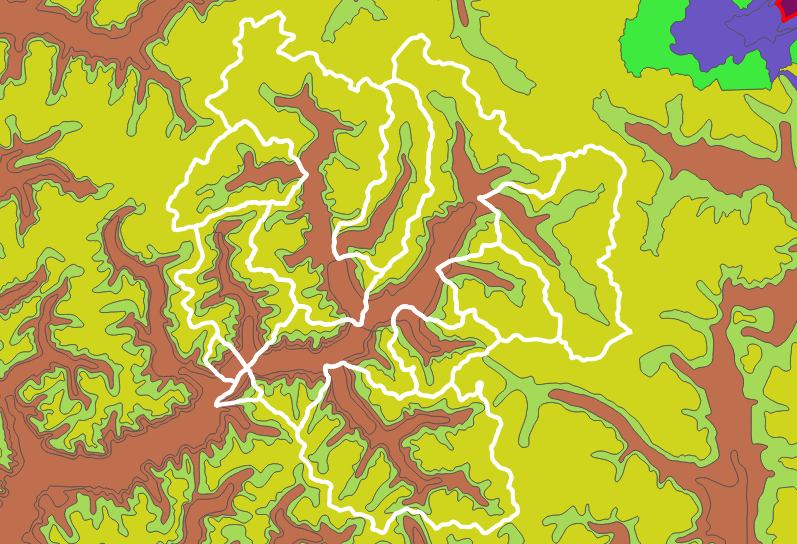

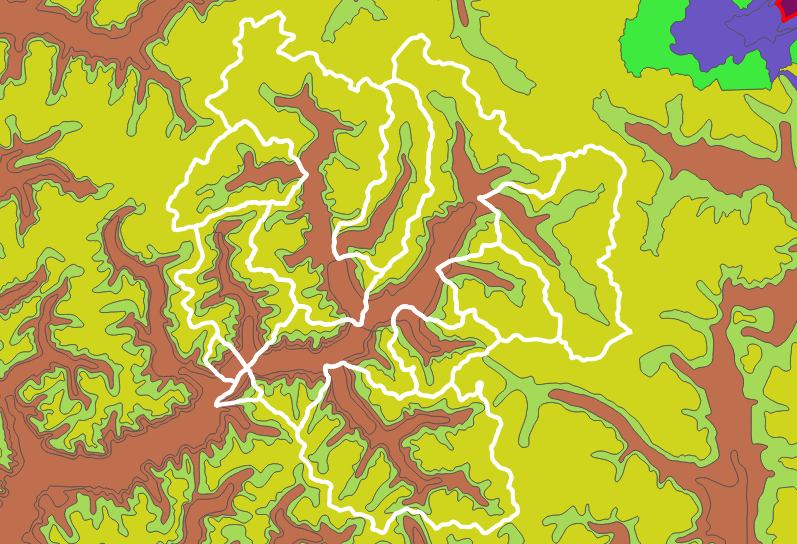

One use of overlay code is chopping large objects up, to find the places they have in common. This query summarizes climate zones (bec) by watershed (wsa).

SELECT

Sum(ST_Area(ST_Intersection(b.geom, w.geom))) AS area_zone,

w.wsd_id,

b.zone

FROM bec b

JOIN wsa w

ON ST_Intersects(b.geom, w.geom)

WHERE w.nwwtrshdcd like '128-835500-%'

GROUP BY 2, 3

The new implementation for this query runs about 2 times faster than the original. Even better, when run on a larger area with more data, the original implementation fails – it’s not possible to get a result out. The new implementation runs to completion.

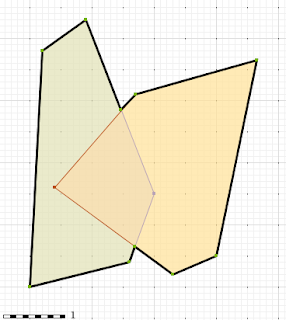

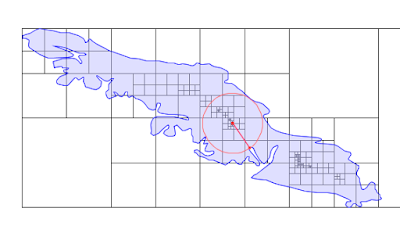

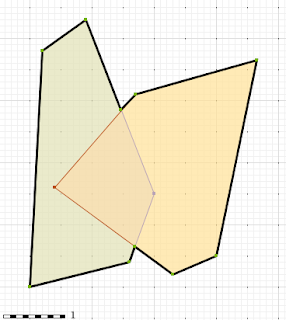

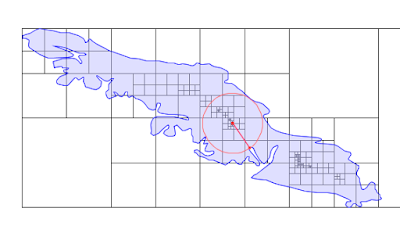

Another common use of overlay code is melting together areas that share an attribute. This query takes (almost) every watershed on Vancouver Island and melts them together.

SELECT ST_Union(geom)

FROM wsa

WHERE nwwtrshdcd like '920-%'

OR nwwtrshdcd like '930-%'

At the start, there are 1384 watershed polygons.

At the end there is just one.

The new implementation takes about 50% longer currently, but it is more robust and less likely to fail than the original.

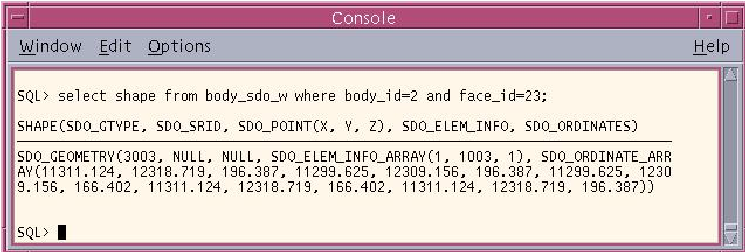

Fixed Precision Overlay

The way Overlay NG ensures robust results, is by falling back to more and more reliable noding approaches. “Noding” refers to how new vertices are introduced into geometries during the overlay process.

- Initially a naive “floating point” noding is used, that just uses double precision coordinates. This works most of the time, but occasionally fails when noding “almost parallel” edges.

- On failure, a “snapping” noding is used, which nudges nearby edges and nodes together within a tolerance. That works most of the time, but occasionally fails.

- Finally, a “fixed precision” noding nudges all of the coordinates in both geometries into a fixed space, where edge collapses can be handled deterministically. This is the lowest performance approach, but it very very rarely occurs.

Sometimes, end users actually prefer to have their geometry forced into a fixed precision grid, and for overlay to use a fixed precision. For those users, with PostGIS 3.1 and GEOS 3.9 there are some new parameters in the intersection/union/difference functions.

The new “gridSize” parameter determines the size of the grid to snap to when generating new outputs. This can be used both to generate new geometries, and also to precision reduce existing geometries, just by unioning a geometry with an empty geometry.

Inscribed Circle

As always, there are a few random algorithmic treats in each new GEOS release. For 3.9, there is the “inscribed circle”, which finds the largest circle that can be fit inside a polygon (or any other boundary).

In addition to making a nice picture, the inscribed circle functions as a measure of the “wideness” of a polygon, so it can be used for things like analyzing river polygons to determine the widest point, or placing labels.