Open Source Debate @ North51

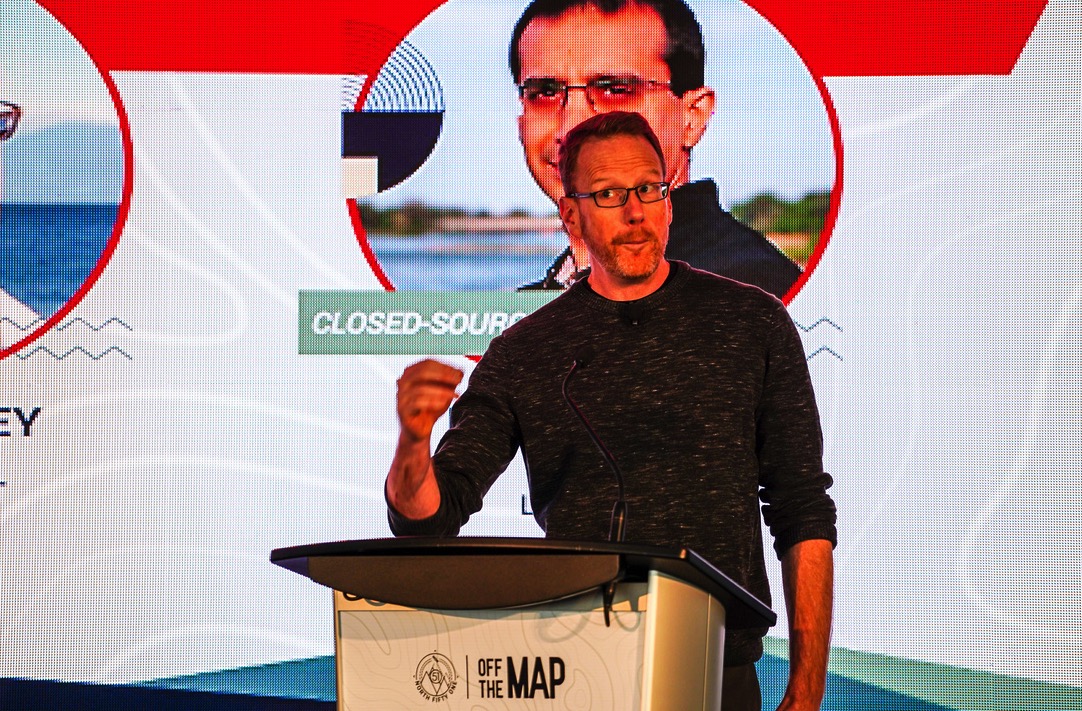

09 Feb 2020In a little change from the usual course of conference structure, I was invited to debate the merits of open source versus proprietary software at the North51 conference in Banff, Alberta last week.

There isn’t a video, but to give you a flavour of how I approached the task, here’s my opening and closing statements:

Opening

Thank you for having me here, Jon, and choosing me to represent the correct side of this argument.

So, to provide a little context, I’d like to start by reading the founding texts of this particular disagreement.

The first text is Bill Gates’ “Open Letter to Hobbyists”, published in the Homebrew Computer Club newsletter in February of 1976, kicking off the era of proprietary software that is still be-devilling us, 45 years later.

“Almost a year ago, Paul Allen and myself, expecting the hobby market to expand, hired Monte Davidoff and developed Altair BASIC. Though the initial work took only two months, the three of us have spent most of the last year documenting, improving and adding features to BASIC… The value of the computer time we have used exceeds $40,000.

“The feedback we have gotten from the hundreds of people who say they are using BASIC has all been positive. Two surprising things are apparent, however, 1) Most of these “users” never bought BASIC and 2) The amount of royalties we have received from sales to hobbyists makes the time spent on Altair BASIC worth less than $2 an hour.

“Why is this? As the majority of hobbyists must be aware, most of you steal your software. Hardware must be paid for, but software is something to share. Who cares if the people who worked on it get paid?

The second text is the initial announcement of the Linux source code, sent by Linus Torvalds in August of 1991

“Hello everybody out there using minix - I’m doing a (free) operating system (just a hobby, won’t be big and professional like gnu) for 386(486) AT clones. … , and I’d like to know what features most people would want. Any suggestions are welcome, but I won’t promise I’ll implement them :-) Linus

After sending these messages, both these technology innovators went on to manage the creation of operating systems that have become dominant, industry standards. Microsoft Windows and Linux.

The difference is that, in the process, Gates became a multi-billionaire and for a time the richest man in the world, while Torvalds is just a garden variety millionaire.

A simple interpretation of this set of facts, of Gates berating hobbyists for “stealing” his software, and of Torvalds welcoming folks to provide him with feature suggestions, is that Gates is a miserable, grasping, corporate greedhead, and Torvalds is a far-seeing, generous, socially conscious computer monk.

There’s something to that.

Still…. A more nuanced view looks at the dates the letters were sent.

In 1976, when Gates sent his letter, the way you built a substantial piece of serious software, is you got 1, 10, 100 programmers together in one building, so you could coordinate their efforts, and you paid them to come in every day and work on it.

And you kept on paying them, until they were done, or done enough to ship, 1, 2 or more months later. And then you made back all that money afterwards, selling many many copies of the software.

This was the shrink-wrap proprietary software model, and it was really easy to understand, because it was exactly the same model used for books, or music, or movies.

Hey… has anyone noticed, a change, in the way we consume books, or music, or movies? Things are different than they were, in 1976. Right?

OK, so what is REALLY different about Torvalds? The difference is manifest in the very way he sent his message. He didn’t mail it to a magazine. He published it electronically, on a Usenet bulletin board, an early mailing list, of Unix operating system enthusiasts, comp.os.minix.

And those enthusiasts joined him in building a complete, open source, operating system. They didn’t have to move to Seattle, and he didn’t have to pay them, and they didn’t have to work on it 8 hours a day, 5 days a week.

They worked on it a bit at a time, in the time they had, and it got bigger.

And eventually it was useful enough the companies started using it, for important things. And they started hiring people to work on it, 8 hours a day, 5 days a week.

But they didn’t have to move to Seattle, either. And they didn’t have to sign over their work to Microsoft, to do the work.

And eventually Linux was so useful that the majority of people working on it were being paid, but not by any one company.

Linus Torvalds works for the Linux Foundation, which is funded by the largest companies in tech.

The top contributors to the Linux kernel in 2017 worked for Intel, Red Hat, Linaro, Samsung, SUSE and IBM. And that only accounts for about 1/3 of contributions… the rest come from a long tail of other contributors.

We’re going to end up talking about definitions and arguing over words a little in this session, I imagine, so I’d like to get one common one out of the way early.

The opposite of “open source” is “proprietary”, not “commercial”. Open source licensing does not foreclose all commercial ventures, it only forecloses those predicated on restricting access to the source code.

You wouldn’t describe my previous employer, Carto, as an “open source company”, they sell geospatial intelligence software as a service. The software they write is all open source licensed and available on Github.

You wouldn’t describe my current employer, Crunchy data as a “non-commercial” entity. We are a private for-profit company, with a corporate headquarters, major clients in government and industry, and a headcount of almost 100.

It’s worth noting that both those employers of mine are headquartered nowhere near where I live, in British Columbia.

That’s not an accident. That really the whole story. It’s the heart of the matter.

The proprietary software model is obsolete.

It is a relic of a bygone age, the pre-internet age.

Before the advent of the internet, the proprietary model was useful to capitalize some forms of large scale software development, but now, in the internet era, it’s mostly an obstacle, a brake on innovation.

Those are some hard words. I know. But if you don’t believe me, maybe ask the number one contributor to open source projects on Github. It’s a little Seattle company called “Microsoft”.

Not only is Microsoft the number one corporate contributor to open source software hosted on Github, they liked Github itself so much they bought the company.

Microsoft knows the future is open source, I know the future is open source, and I hope by the time we’re done you all know the future is open source.

Closing

I know there is proprietary software in the world.

I am not saying there is no place for proprietary software in the world.

Some of my best friends use proprietary software.

I do not harangue them, I do not put them down.

Well, not to their faces, anyways.

What I do know is that the system of proprietary software is a system in which all the incentives align towards passivity, towards stagnation, and away from innovation.

Proprietary vendor’s incentives are to lock customers in, and to drive customers towards further purchases of more product.

This leads to less interoperability.

It leads to less efficient software.

It leads to artificial boundaries in functionality, between “Basic” versions and “Pro” versions and “Enterprise” versions – boundaries predicated on nothing but revenue maximization.

Customers dependent on proprietary software lose their agency in improving their tools. They adopt poor systems designs to fit their software use within the terms of their license limits.

They stop thinking that their tools could be something other than what the vendor says they are.

They lose their freedom.

- As a society, we should bias toward a software development model that maximizes innovation. Open source is that model.

- As organizations, we should bias toward a software development model and tools that maximize flexibility and cooperation. Open source is that model.

- As individuals, we should bias towards tools that maximize our ability to move our skills from employer to employer, regardless of what vendor they happen to use. Open source provides those tools.

Embrace your power, embrace your freedom, embrace open source.