08 Jan 2025

I did a lot of reading last year, a lot, perhaps because I had a lot of down time. I tend to read before going to sleep, and recovery from surgery and other things means I go to bed early and then fill the time between bed and sleep with books. Books, books, and more books.

To be totally precise, I read books on a Kindle, which allows me to read in the middle of the night in the dark with the back light. Also to read from any position, since all books are the same, light weight when consumed via an e-reader. I am a full e-reader convert.

Anyway, I’ve had means, motive and opportunity, and I read a tonne. Some of it was bad, some of it was good, some of it was memorable, some not. Of the 50 or so books I read last year, here are ten that made me go “yes, that was good and memorable”.

Demon Copperhead, Barbara Kingsolver

I used to read Booker Prize winners, but I found the match to my taste was hit-and-miss. The Pullitzer Prize nominees list, on the other hand, has given me piles of great reads. I am still mining it for recommendations, older and older entries.

Anyways, this modern day re-telling of Dicken’s David Copperfield is set in Apallacia, amid the height of the opiod crises. The book is tightly written, has some lovely turns of phrase, and a nice tight narrative push, thanks to the borrowed plot structure. I re-read the Dickens after, because it was so much fun to mark out the character borrowings and plot beats.

Master Slave, Husband Wife, Ilyon Woo

This non-fiction re-telling of an earlier first person account is occasionally verbose, but an excellent entrant into a whole category of writing I did not know existed, the contemporaneous slavery escape narrative. For obvious reasons, abolitionists before the Civil War were keen to promote stories that humanized the people trapped in the south, who might otherwise be theoretical to Northern audiences.

The book re-tells the escape of Ellen and William Craft, and wraps that story in a lot of historical context about the millieu they were escaping from (antebellum Georgia) and to (abolitionist circles in the North). The actual text of their story is liberally quoted from, but this is a re-telling. Frederick Douglass appears in their story, which gave me the excuse I have been waiting for a long time to read the next book in this list.

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass

It took me way too long to finally pick up this book, given that Douglass has showed up as such an important figure in the other historical books I have read: Team of Rivals, Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant, And There Was Light.

One goes into books from the 1800s wondering just how punishing the language is going to be. Clauses upon subclauses upon subclauses? None of that here. Douglass writes wonderfully clean prose the modern mind can handle, and tells his story with economy but still enough context to make it powerful. Probably because as a master story teller, he was pitching for an audience much like the modern one – made up of people with little knowledge of the particulars of the slave system, just a broad and overly simple sense of the injustice. After 150 years, still devestating and accessible.

How Much of These Hills Is Gold, C Pam Zhang

The Goodreads crew does not seem to think this book is as good as I do, but what strikes me about it and what makes me slot it into my “years best” is that I remember it so clearly. This is a historical novel of the California gold rush, from the eyes of children born to Chinese immigrants in the gold fields. It’s both an intense family drama, and an meditation on the power of place. It left me with a strongly remembered sense of the land, and the characters. Even though it covers a big swathe of years, the cast of characters remains small and their interactions meaningful. It’s memorable!

(Also, and this is no small thing, I read Into the Distance by Hernan Diaz this year too, which is set in the same time period and has some of the same beats… so maybe these books are a pairing.)

Julia, Sandra Newman

It’s a great time to be reading about authoritarianism! In the same spirit as pairing up Demon Copperhead with David Copperfield, I also paired up a reading of George Orwell’s 1984 with this retelling of the same story from the point of view of Julia, the love interest in Orwell’s book.

Newman takes the opportunity to flesh out Julia as a character and also the world of 1984 a little more, which makes the re-read of the original really fun. I do not think I noticed before just how much Winston Smith is a self-absorbed schmuck, but once you’ve seen it, you cannot unsee it.

The Bee Sting, Paul Murray

A tragedy told from the inter-leaved view points of four members of a family falling apart. Each chapter from a different character, each builds up the point of view narrator and also illuminates the others. Mostly the reveal is who these people are, bit by bit, but the plot also slowly clicks together like a puzzle until that last piece slides in, and oh boy.

An easy engaging read that gets more and more intense, but you cannot look away.

Yellowface, R F Huang

Written by an Asian-American author, about a white author appropriating the story of an Asian-American author, the story is gripping, snarky, and unblinking in its takedown of the publishing industry. Come for the plot, stay for the commentary on modern meme-making and self-promotion, the intersection between who we are and who we present ourselves as. On the internet, nobody knows you are a dog. Or everybody knows you are a dog and hates you for it.

The Librarianist, Patrick deWitt

I don’t think this book made many or any “best of” lists, so it is not clear to me what caused me to read it, but it was a treat. Just a very quiet story about an introverted retired librarian, finding his way as he transitions into retirement, and builds some new connections with his community. Sounds really boring, I know, but I hoovered it up and it still sticks with me. A good read if you need some optimism and calm in your life.

Say Nothing, Patrick Radden Keefe

A history of the Troubles in Ireland, wrapped around the story of a particular murder, long unsolved, that slowly reveals itself over the decades, as the perpetrators come to terms with their part in that violent chapter of history. The Goodreaders really like this one and I agree. I knew the bare minimum of this chapter of world history (what I gleaned from CNN at the time, and from Derry Girls more recently) and this telling makes an easy introduction, covering a wide sweep of time and context.

Notes from the Burning Age, Claire North

Claire North remains a lesser-known science fiction author, despite her low-key hit The First Fifteen Lives of Harry August (read it!), but I’m a convert, and this novel reminded me why. The world is a post-climate crisis culture that has achieved some spiritual and technological balance with the ecology, but is wrestling with the return of what we would describe as “business as usual” – the subjugation of the natural world to the needs of humans.

Following an ecological monk, turned spy, from inside the capital of the new humanists, through the other realms of this world is easy because the journey is wrapped in a high-stakes espionage story. Of all the climate stories I have read lately, this one taken from such a long distance in the future speaks to me most. I want to think we will build something new and better, and while I know our human nature can be malign, I also know it can be beautiful.

Trust, Hernan Diaz

Best for last. Told in multiple sections from multiple perspectives in multiple styles, every narrator is unreliable, each in their own way, but the idea that there is a kernel of truth lying beneath it all never goes away (and yet, is never truly revealed). Perhaps a perfect book club novel for that reason. (Not where I got it, it’s another Pullitzer winner.)

Some facts everyone agrees on. There is a very rich and powerful financier. He has a relationship with a woman who he marries who is very important to him. But in what way? Unclear. And man is malign, but in what ways? The usual mercenary ones you might expect of a Wall Street lion? Worse and additional ways? Unclear. The whole thing is a puzzle box, the language, the characters, the events. Read it. Read it again. Read it a third time.

30 Sep 2024

Back to entry 1

I was glancing at the New York Times and saw that Catherine, the Princess of Wales, had released an update on her treatment. And I thought, “wow, I hope she’s doing well”. And then I thought, “wow, I bet she gets a lot of positive affirmation and support from all kinds of people”.

I mean, she’s a princess.

Even us non-princesses, we need support too, and I have to say that I have been blown away by how kind the people around me in my life have been. And also how kind the other folks who I have never really talked with before have been.

I try to thank my wife as often as I can. It is hard not to feel like a burden when I am, objectively, a burden, no matter how much she avers I am not. I am still not fully well (for reasons), and I really want to be the person she married, a helpful full partner. It is frustrating to still be taking more than I’m giving.

From writing about my experience here, I have heard from other cancer survivors, and other folks who have travelled the particular path of colorectal cancer treatment. Some of them I knew from meetings and events, some from their own footprint on the internet, some of them were new to me. But they were all kind and supportive and it really helped, in the dark and down times.

From my work on the University of Victoria Board of Governors, I have come to know a lot of people in the community there, and they were so kind to me when I shared my diagnosis. My fellow board members stepped in and took on the tasks I have not been able to do the past few months, and the members of the executive and their teams were so generous in sending their well-wishes.

And finally, my employers at Crunchy Data were the best. Like above and beyond. When I told them the news they just said “take as much time as you need and get better”. And they held to that. My family doctor asked “do you need me to write you a letter for your employer” and I said “no, they’re good”, and he said, “wow! don’t see that very often”. You don’t. I’m so glad Crunchy Data is still small enough that it can be run ethically by ethical people. Not having to worry about employment on top of all the other worries that a cancer diagnosis brings, that was a huge gift, and not one I will soon forget.

I think people (and Canadians to a fault, but probably people in general) worry about imposing, that communicating their good thoughts and prayers could be just another thing for the cancer patient to deal with, and my personal experience was: no, it wasn’t. Saying “thanks, I appreciate it” takes almost no energy, and the boost of hearing from someone is real. I think as long as the patient doesn’t sweat it, as long as they recognize that “ackknowledged! thanks!” is a sufficient response, it’s all great.

Fortunately, I am not a princess, so the volume was not insuperable. Anyways, thank you to everyone who reached out over the past 6 months, and also to all those who just read and nodded, and maybe shared with a friend, maybe got someone to take a trip to the gastroenterologist for a colonoscopy.

Talk to you all again soon, inshala.

24 Sep 2024

Back to entry 1

What happened there, I didn’t write for three months! Two words: “complications”, and “recovery”.

In a terrifying medical specialty like cancer treatment, one of the painful ironies is that patients spend a lot of time suffering from complications and side effects of the treatments, rather than the cancer. In my case and many others, the existence of the cancer isn’t even noticable without fancy diagnostic machines. The treatments on the other hand… those are very noticable!

A lot of this comes with the territory of major surgery and dangerous chemicals. My surgery included specific possible complications including, but not limited to: incontinence, sexual disfunction, urinary disfunction, and sepsis.

Fortunately, I avoided all the complications specific to my surgery.

What I did not avoid was a surprisingly common complication of spending some time in a hospital while taking broad spectrum antibiotics–I contracted the “superbug” clostridioides difficile, aka c.diff.

Let me tell you, finding you have a “superbug” is a real bummer, and c.diff lives up to its reputation. Like cancer, it is hard to kill, it does quite a bit of damage while it’s in you, and the things that kill it also do a lot of damage to your body.

Killing my c.diff required a couple of courses of specialized antibiotics (vancomycin), that in addition to killing the c.diff also killed all the other beneficial bacteria in my lower intestine.

So, two months after surgery, I was recovering from:

- having my lower intestine handled and sliced in a major surgery

- having that same intestine populated with c.diff and covered in c.diff toxins

- having the microbiotic population living in my intestine nuked with a modern antibiotic developed to kill resistant superbugs

Not surprisingly, having all those things at once makes for a much longer recovery, and a pretty up-and-down one. My slowly recovering microbiota is in constant flux, which results in some really surprising symptoms.

- highly variable stomach discomfort (ok)

- highly variable appetite (makes sense)

- random days of fatigue (really?)

- random days of anxiety (what?!?)

I had not really understood the implications of gut/brain connection, until this journey showed me just how tightly bound my mental state was to the current condition of my guts. The anxiety I have experienced as a result of my c.diff exposure has been worse, amazingly, than what I felt after my initial cancer diagnosis. One was in my head, but the other was in my gut.

I have also developed a much more acute sympathy for people suffering from long Covid and other chronic diseases. The actual symptoms are bad enough, but the psychological effect of the symptom variability is really hard to deal with. Bad days follow good days, with no warning. I have mostly stopped voicing any optimism about my condition, because who knows what tomorrow will bring.

When people ask me how I’m doing, I shrug.

One thing I have got going for me, that chronic disease sufferers do not, is a sense that I am in fact improving. I started journaling my symptoms early in the recovery process, and I can look back and see definitively that while things are unpredictable day to day, or even week to week, the long term trajectory is one of improvement.

Without that, I think I’d go loopy.

Anyways, I am now rougly three months out from my last course of antibiotics, and I expect it will be at least another three months before I’m firing on all cylinders again, thanks mostly to the surgical complication of acquiring c.diff. If I was just recovering from the surgery, I imagine I would be much closer to full recovery.

01 Jun 2024

Back to entry 1

So, I got the news from pathology.

There is no cancer left in me, I am officially “cured”.

Since I am still recovering from surgery and relearning what my GI tract is going to do for the future, I don’t feel entirely cured, but I do feel the weight of wondering about the future lifted off of me.

The future will not hold any more major cancer treatments, just annual screening colonoscopies, and getting better post-surgery.

I truly have had the snack-sized experience, not that I would recommend it to anyone. Diagnosed late February, spit off the back of the conveyor belt in late May. Three months in Cancerland, three months too many.

A few days ago NBA great Bill Walton died of colorectal cancer. It’s the second most common cancer in both men and women, and you can avoid a trip to Cancerland through the simple expedient of getting screened. Don’t skip it because you are young, colorectal cancer rates amount people under 50 are going up fast, and nobody knows why (there’s something in the environment, probably).

13 May 2024

Back to entry 1

Scanxiety.

This is where I am right now. Scanxiety.

Each stage of the cancer experience is marked by a particular set of tests, of scans.

I actually managed to get through my first set of scans surprisingly calmly. After getting diagnosed (“there’s some cancer in you”), they send you for “staging”, which is an MRI and CT scan.

These scans both involve large, Star Trek seeming machines, which make amazing noises, and in the case of the CT machine I was put through was decorated with colorful LED lights by the manufacturer (because it didn’t look whizzy enough to start with?).

I kind of internalized the initial “broad-brush” staging my GI gave me, which was that it was a tumor caught early so I would be early stage, so I didn’t worry. And it turned out, that was a good thing, since the scans didn’t contradict that story, and I didn’t worry.

The CT scan, though, did turn up a spot on my hip bone. “Oh, that might be a bone cancer, but it’s probably not.” Might be a bone cancer?!?!?

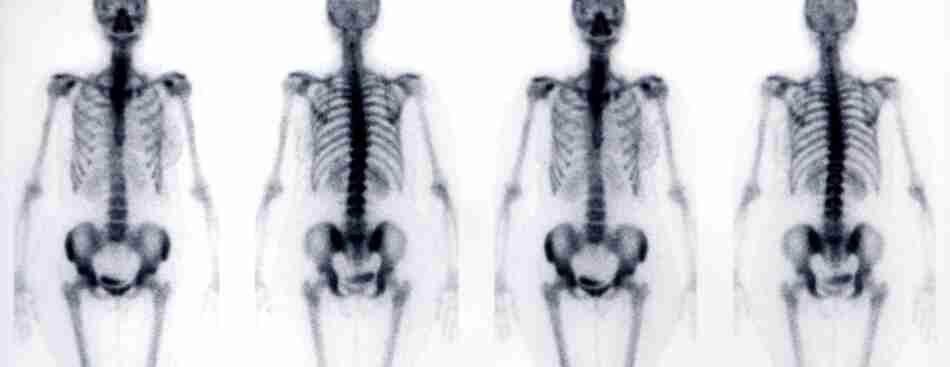

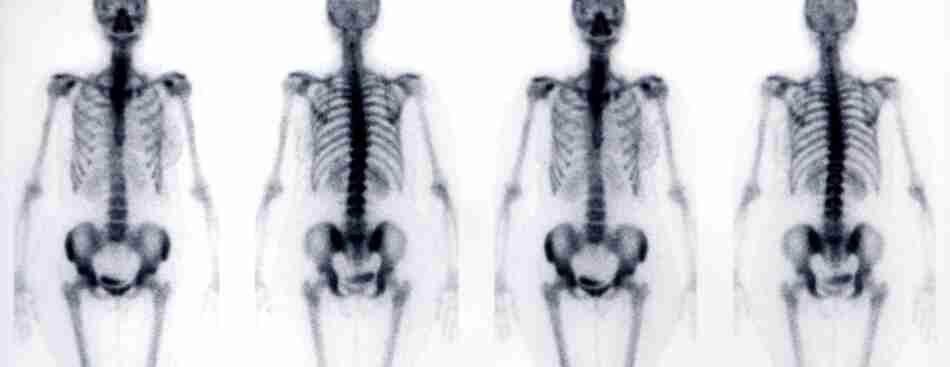

How do you figure out if you have “a bone cancer, but it’s probably not”? Another cool scan, a nuclear scan, involving being injected with radioactive dye (frankly, the coolest scan I have had so far) and run through another futuristic machine.

This time, I really sweated out the week between the scan being done and the radiology coming back. And… not bone cancer, as predicted. But a really tense week.

And now I’m in another of those periods. The result of my major surgery is twofold: the piece of me that hosted my original tumor is now no longer inside of me; and, the lymph nodes surrounding that piece are also outside of me.

They are both in the hands of a pathologist, who is going to tell me if there is cancer in the lymph nodes, and thus if I need even more super unpleasant attention from the medical system in the form of several courses of chemotherapy.

The potential long term side effects of the chemotherapy drugs used for colorectal cancers include permanent “peripheral neuropathy”, AKA numbness in the fingers and toes. Which could put a real crimp in my climbing and piano hobbies.

So as we get closer to getting that report, I am experiencing more and more scanxiety.

If I escape chemo, I will instead join the cohort of “no evidence of disease” (NED) patients. Not quite cured, but on a regular diet of blood work, scans, and colonoscopy, each one of which will involve another trip to scanxiety town. Because “it has come back” starts as a pretty decent probability, and takes several years to diminish to something safely unlikely.

Yet another way that cancer is a psychological experience as well as a physical one.

Talk to you again soon, inshalla.