16 Apr 2024

Back to entry 1

A common refrain on my Facebook cancer support groups is that the first months after diagnosis can be among the most stressful. You know the least about the actual extent of your condition, but you simultaneously know for sure that your life is going to change a great deal, starting now.

It is also the first time for grieving.

In the worst case it is grieving actual mortality, the very real threat of the end. But even in a relatively low impact diagnosis like my (current) one, there is grief. It is the grief of lost futures, lost plans, lost self-image.

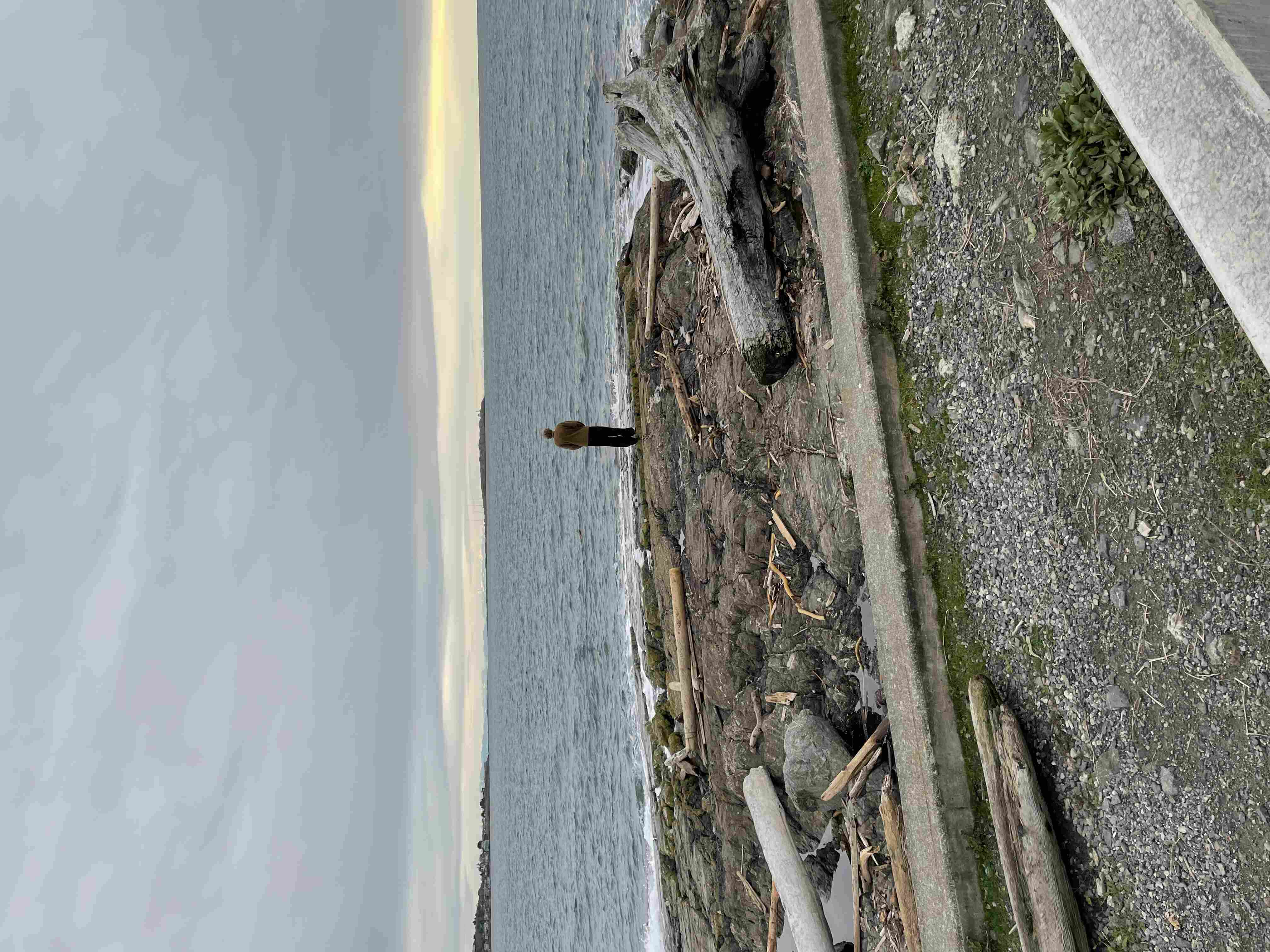

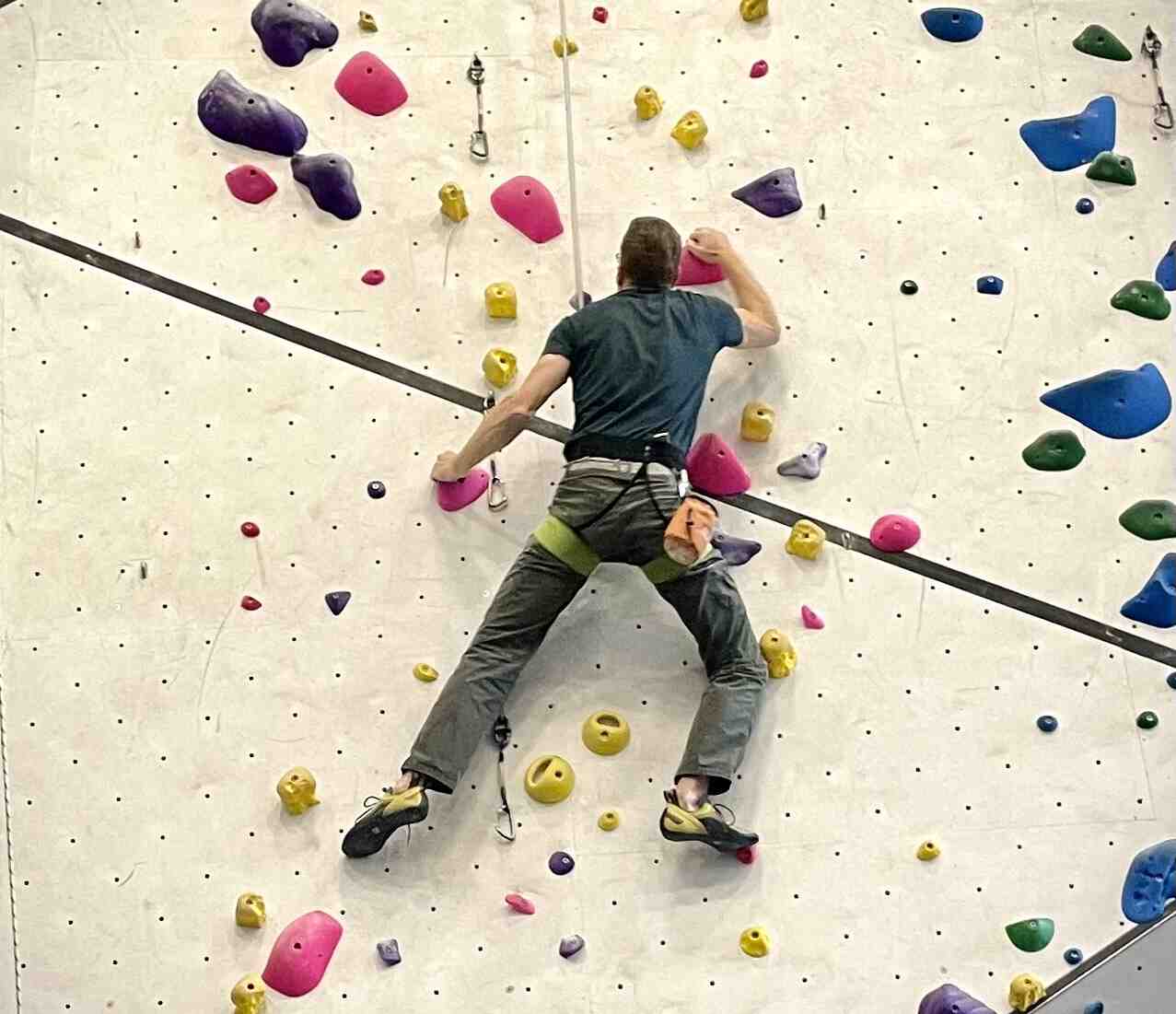

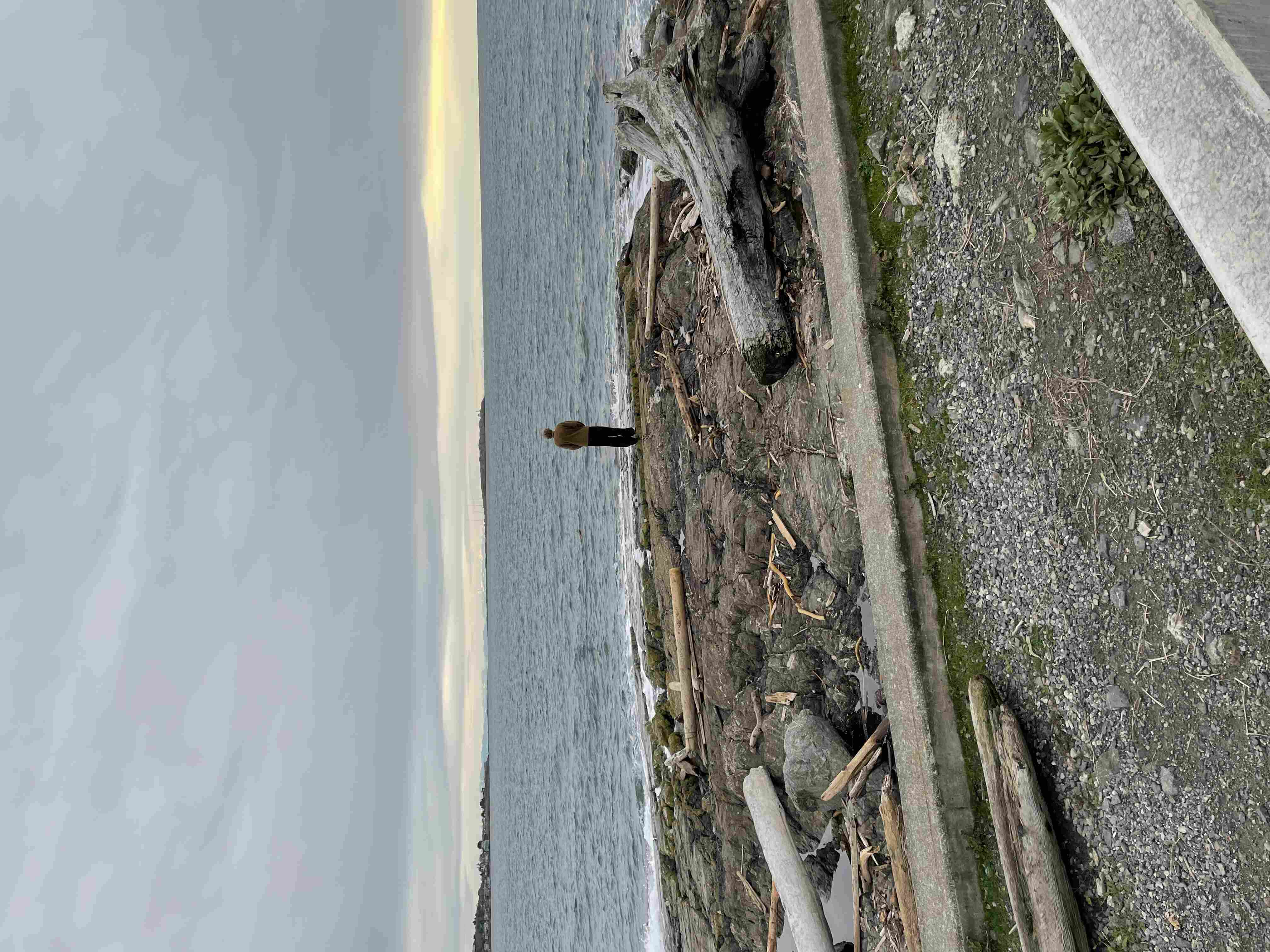

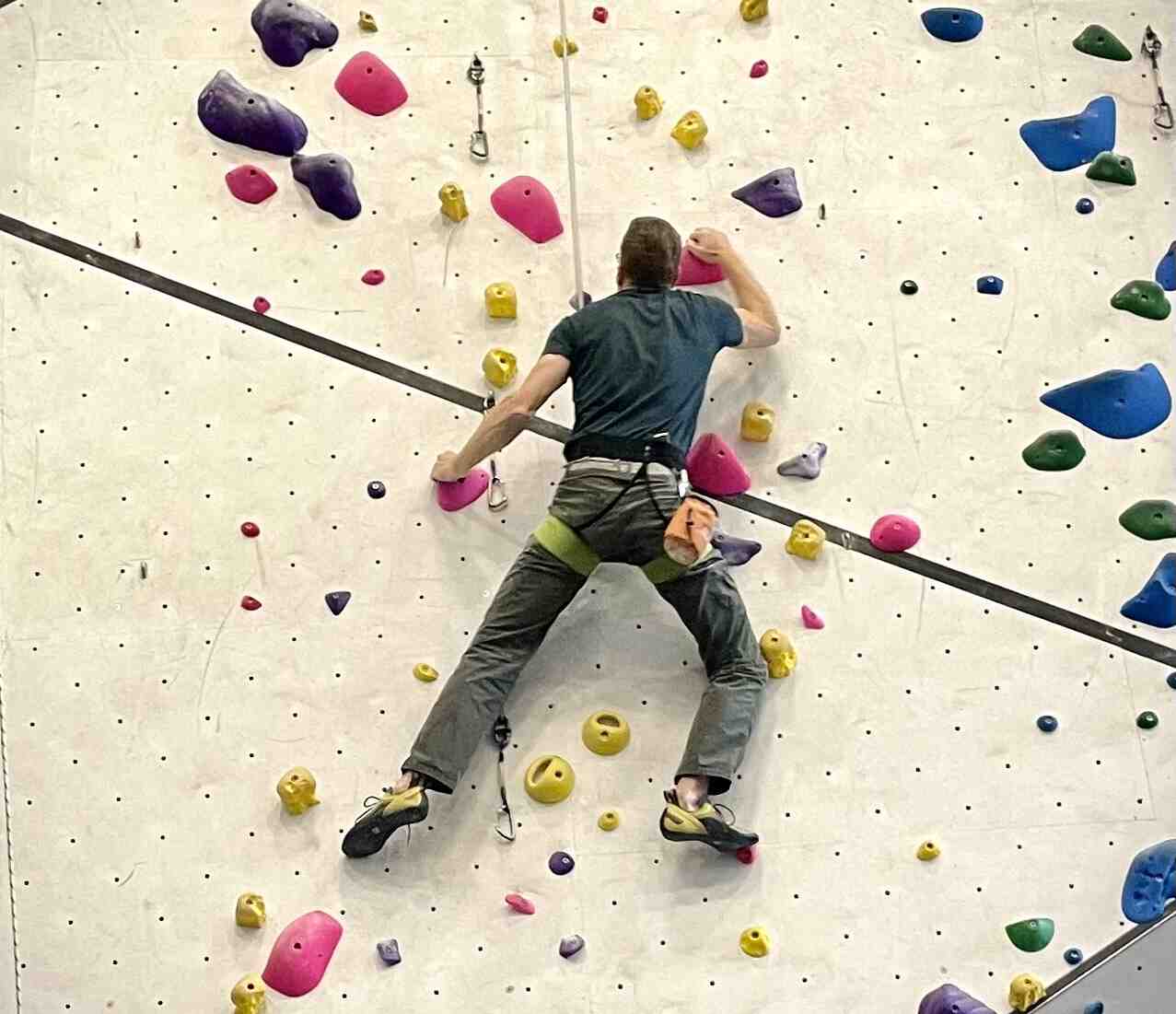

I am a person who runs and climbs and rows and goes on long walks and travels and teaches and speaks publicly. At least, I was. If all goes according to plan, there will eventually be a new me, who does some or many of those things. Maybe not all of them anymore, there is no predictability or control.

Last Christmas I took my family to Rome over the holidays. “No time like the present!” I said, little knowing how apt that would be. I’m glad for everything I have done with my family. Climbing mountains, scaling cliffs, travelling afar, and even the predictable summer trips to the beach.

Some of these adventures were quite hard, and in the moment I wondered to myself “what the heck were you thinking?” In the end, I regretted none of it, and we all have lifelong memories we share.

Before she was killed by cancer, Amy Ettinger wrote:

I’ve always tried to say yes to the voice that tells me I should go out and do something now, even when that decision seems wildly impractical … Money always comes back, but if you miss out on an experience, the opportunity may never come back.

I am trying to pack as much climbing, and eating out, and walks to the cafe, and evening date nights into my life as I can, before the start of treatment. It’s too late for anything big, but these are little things that bring me joy that may become harder to do, after.

My surgery date is set now, and the procedure will mark an abrupt decline and then the start of a long slow climb back up to whatever “new normal” my body can fashion from my reconfigured plumbing. Some people have great results, some people have terrible ones.

As always, there’s no way to know, the grey area is omnipresent, which is perhaps why I sound so morose.

Talk to you again soon, inshalla.

14 Apr 2024

Back to entry 1

Before I joined the population of fellow cancer travellers, I had the same simple linear understanding of the “process” that most people do.

You get diagnosed, you get treatment, it works or it doesn’t.

What I didn’t appreciate (and this will vary from cancer to cancer, but my experience is with colorectal) is how little certainty there is, and how wide the grey areas are.

Like, in my previous post, I said I was “diagnosed” with cancer. Which maybe made you think I have it. But that’s not how it works. I had a colonoscopy, and a large polyp was removed, and that polyp was cancerous, and a very small part of it could not be excised. So it’s still in me.

Do I have cancer? Maybe! I have a probability of having live cancer cells in me that is significantly higher than zero. But not as high as one.

How bad is what I (might) have? This is also a game of probability. Modern technology can shave off the edges of the distribution, but it can’t quite nail it down.

A computed tomography (CT) scan didn’t show any other tumors in my body, so that means I probably don’t have “stage 4” (modulo the resolution of the scan), which is mostly incurable (though it can be manageable), where the cancer has managed to spread outside the colon.

An MRI didn’t show any swollen lymph nodes, which means I maybe do not have “stage 3”, which requires chemotherapy, because the cancer has partially escaped the colon. But MRI results are better at proving rather than disproving nodal involvement and people report having surgical results that run counter to the MRI all the time.

That leaves me (theoretically) at “stage 2”, looking at a surgical “cure” that involves removing the majority of my rectum and a bunch of lymph nodes. At that point (after the major life-altering surgery!) the excised bits are sent to a pathologist, and the probability tree narrows a little more. Either the pathologist finds cancer in the nodes (MRI was wrong), and I am “upstaged” to stage 3 and sent to chemotherapy, or she doesn’t and I remain a stage 2 and move to a program of monitoring.

In an exciting third possibility, the pathologist finds no cancer in the lymph nodes or the rectum, which means I will have had major life-altering surgery to remove… nothing dangerous. My surgeon says I should find this a happy result (no cancer!) which is probably because he’s seen so many unhappy results, but it’s a major surgery with life-long side effects and I would do almost anything to not have to have it.

Amazingly, despite our modern technology there’s just no way to know for sure if there are still live cancer cells in me short of taking the affected bits out and doing the pathology. Or waiting to see if something grows back, which is to flirt with a much worse prognosis.

Monitoring will be regular blood tests, annual scans and colonoscopies for several years, as the probability of recurrence slowly and asymptotically moves toward (but never quite arrives at) zero. And all those tests and procedures have their own error rates and blind spots.

There are no certainties. All the measuring and cutting and chemicals, and I will still have not driven the cancer entirely out, it will stubbornly remain as a probability, a non-zero ghost haunting me every year of the rest of my hopefully long life.

And of course worth mentioning, I am getting the snack-sized, easy-mode version of this experience! People in stage three or stage four face a probability tree with a lot more “and then you probably die in a few years” branches, and the same continuous reevaluation of that tree, with each new procedure and scan, each new discovery of progression or remission.

Talk to you again soon, inshalla.

10 Apr 2024

A little over a month ago, three days after my 53rd birthday, I received a diagnosis of rectal cancer. Happy birthday to me.

Since then, I have been wrestling with how public to be about it. I have a sense that writing is good for me. But it also keeps like milk. I wrote most of this a couple weeks ago and my head space has already evolved.

So writing like this is mostly a work of self-absorption (I’m sure you can forgive me) but hopefully it also helps to raise awareness amongst the cohort of people who might know me or read this.

Colorectal cancer rates are going up, and the expected age of occurance is going down. Please get screened. No matter your age, ask your clinician for a “FIT test”. If you’re over 45, just ask for a colonoscopy, the FIT test isn’t perfect.

I have a pretty good prognosis, mostly because my case was caught by screening, not by experiencing symptoms bad enough to warrant a trip to the doctor. Most of the people who get diagnosed after showing symptoms have it worse than I, and will have a longer, harder road to recovery. Get screened.

Our language of cancer borrows a bit from the language of contagion. I “got” cancer. It’s not quite a neutral description, there’s a hint of agency in there, maybe I did something wrong? This article drives me crazy, the author “went vegan and became a distance runner” after his father died of colorectal cancer.

Sorry friend, cancer is not something you “get”, and it’s not something you can opt out of with clean living. It’s something that happens to you. Take it from this running, cycling, ocean rowing, rock climbing, healthy eater – driving down the marginal probability of cancer (and heart disease (and depression (and more))) with exercise and diet is its own reward, but you are not in control. When cancer wants you, it will come for you.

This is why you should get screened (right?). It’s the one way to proactively protect yourself. The amazing thing about a colonoscopy is, not only can it detect cancer, it can also prevent it, by removing pre-cancerous polyps. It’s possible that screening could have prevented my case, if I had been screened a few years earlier.

I am now a denizen of numerous Facebook fora for fellow travellers along this life path, and one of the posts last week asked “what do you think cancer taught you”? I am a little too early on the path to write an answer myself, but one woman’s answer struck me.

She said it taught her that control is an illusion.

Before, I had plans. I could tell you I was going to go places, and do things, and when I was going to do them, next month, next season, next year. I was in control. Now, I can tell you what I will be doing next week. Perhaps. The rest is in other hands than mine.

Talk to you again soon, inshalla.

06 Feb 2024

Update: The programme is now public.

The programme for pgconf.dev in Vancouver (May 28-31) has been selected, the speakers have been notified, and the whole thing should be posted on the web site relatively soon.

I have been on programme committees a number of times, but for regional and international FOSS4G events, never for a PostgreSQL event, and the parameters were notably different.

The parameter that was most important for selecting a programme this year was the over 180 submissions, versus the 33 available speaking slots. For FOSS4G conferences, it has been normal to have between two- and three-times as many submissions as slots. To have almost six-times as many made the process very difficult indeed.

Why only 33 speaking slots? Well, that’s a result of two things:

- Assuming no more than modest growth over the last iteration of PgCon, puts attendence at around 200, which is the size of our plenary room. 200 attendees implies no more than 3 tracks of content.

- Historically, PostgreSQL events use talks of about 50 minutes in length, within a one hour slot. Over three tracks and two days, that gives us around 33 talks (with slight variations depending on how much time is in plenary, keynotes or lightning talks).

The content of those 33 talks falls out from being the successor to PgCon. PgCon has historically been the event attended by all major contributors. There is an invitation-only contributors round-table on the pre-event day, specifically for the valuable face-to-face synch-up.

Given only 33 slots, and a unique audience that contains so many contributors, the question of what pgconf.dev should “be” ends up focussed around making the best use of that audience. pgconf.dev should be a place where users, developers, and community organizers come together to focus on Postgres development and community growth.

That’s why in addition to talks about future development directions there are talks about PostgreSQL coding concepts, and patch review, and extensions. High throughput memory algorithms are good, but so is the best way to write a technical blog entry.

Getting from 180+ submissions to 33 selections (plus some stand-by talks in case of cancellations) was a process that consumed three calls of over 2 hours each and several hours of reading every submitted abstract.

The process was shepherded by the inimitable Jonathan Katz.

- A first phase of just coding talks as either “acceptable” or “not relevant”. Any talks that all the committee members agreed was “not relevant” were dropped from contention.

- A second phase where each member picked 40 talks from the remaining set into a kind of “personal program”. The talks with just one program member selecting them were then reviewed one at a time, and that member would make the case for them being retained, or let them drop.

- A winnow looking for duplicate topic talks and selecting the strongest, or encouraging speakers to collaborate.

- A third “personal program” phase, but this time narrowing the list to 33 talks each.

- A winnow of the most highly ranked talks, to make sure they really fit the goal of the programme and weren’t just a topic we all happened to find “cool”.

- A talk by talk review of all the remaining talks, ensuring we were comfortable with all choices, and with the aggregate make up of the programme.

The programme committee was great to work with, willing to speak up about their opinions, disagree amicably, and come to a consensus.

Since we had to leave 150 talks behind, there’s no doubt lots of speakers who are sad they weren’t selected, and there’s lots of talks that we would have taken if we had more slots.

If you read all the way to here, you must be serious about coming, so you need to register and book your hotel right away. Spaces are, really, no kidding, very limited.

07 Jan 2024

This year, the global gathering of PostgreSQL developers has a new name, and a new location (but more-or-less the same dates) … pgcon.org is now pgconf.dev!

Some important points right up front:

- The call for papers is closing in one week! If you are planning to submit, now is the time!

- The hotel scene in Vancouver is competitive, so if you put off booking accomodations… don’t do that! Book a room right away.

- The venue capacity is 200. That’s it, so once we have 200 registrants, we are full for this year. Register now.

- There are also limited sponsorship slots. Is PostgreSQL important to your business? Sponsor!

I first attended pgcon.org in 2011, when I was invited to keynote on the topic of PostGIS. Speaking in front of an audience of PostgreSQL luminaries was really intimidating, but also gratifying and empowering. Notwithstanding my imposter syndrome, all those super clever developers thought our little geospatial extension was… kind of clever.

I kept going to PgCon as regularly as I was able over the years, and was never disappointed. The annual gathering of the core developers of PostgreSQL necessarily includes content and insignts that you simply can not come across elsewhere, all compactly in one smallish conference, and the hallway track is amazing.

PostgreSQL may be a global development community, but the power of personal connection is not to be denied. Getting to meet and talk with core developers helped me understand where the project was going, and gave me the confidence to push ahead with my (very tiny) contributions.

This year, the event is in Vancouver! Still in Canada, but a little more directly connected to international air hubs than Ottawa was.

Also, this year I am honored to get a chance to serve on the program committee! We are looking for technical talks from across the PostgreSQL ecosystem, as well as about happenings in core. PostgreSQL is so much larger than just the core, and spreading the word about how you are building on PostgreSQL is important (and I am not just saying that as an extension author).

I hope to see you all there!